High Expectations Case Studies

Every year across the globe, teachers make a huge impact on the lives of the students they teach.

This month, we would like to share the stories of ordinary teachers who achieved what appear to be extraordinary results with low performing students.

However, you will find that with the right tools and commitment, it is within all of our reach to change both our own and our students' mindsets around the negative beliefs that are holding us back, and to make what now seems extraordinary, the ordinary.

It is within all of our reach to change both our own and our students' mindsets around the negative beliefs that are holding us back. |

The teachers and administrators highlighted here, all part of our High-Expectations Course, made a commitment to the following things:

- To get a low-performing student to outperform his/her stereotype of him/herself by sending high-expectations messages:

- What we’re doing is important.

- You can do it.

- I’m not going to give up on you.

- Effective effort is the key to achievement.*

- To open up their practice to experiment with the plethora of skills contained within the professional knowledge base of high-expertise teaching.

And along the way, the participants in these cases examined their beliefs about intelligence, effort, and ability - both of their students and of their own!

*Jeff Howard is the father of this concept and these words. He has been teaching them for over a quarter of a century. We are now seeing this idea enter the conventional wisdom, often without attribution.

There is a tap root of belief about students’ capacity that underlies all these stories: the belief that ability is malleable, that “smart is something you can get.” We have in this country an erroneous view of the role of “innate ability” (read as intelligence), in school learning and life success. (See Expectations chapter in The Skillful Teacher for a complete history of this concept.)

Yes, there are differences in predispositions for certain kinds of learning. Yes, motivation varies greatly. Yes, certain students come to school with tremendous disadvantages. But they all can accelerate their learning and can meet standards. We can teach students to be motivated. It is part of our job.

Not all the educators profiled here started out believing the above. But they do all have perseverance. The students they are working with are not easy cases. They are all discouraged, sometimes angry, almost always academically way behind. And they are used to adults giving up on them. These teacher and administrators do not.

These are inspiring stories for several reasons:

- First, we see profound changes in children’s belief in themselves, in their motivation to learn, and in their academic achievement.

- Second, we see the teachers quickly generalize the strategies to other students. The case study winds up affecting many more than the one student who is its subject.

- Third, it is clear what these teachers did, and there is nothing extraordinary or heroic about it. Readers will quickly say: “I could do that!

Or, as we put it:

This is important. You can do it! I won’t give up on you! |

Focused Feedback - Kindergarten

What I tried:

For this experiment I decided to focus on a low-confidence/low-performing student in my kindergarten classroom that I believed could benefit from positive and useful feedback. Therefore, I chose to focus my attention on how I use feedback and what messages I am sending through my feedback.

I began the experiment by eliminating messages such as "good job”, “nice work", and "nice try" and replacing them with more direct, focused feedback messages like: “I can see that you really put a lot of effort into this picture!" and "Look at what you accomplished by not giving up; you should be so proud of this!"

I began the experiment by eliminating messages such as "good job”, “nice work", and "nice try" and replacing them with more direct, focused feedback messages. |

How it went:

I started implementing the strategy of focused and effective feedback in the middle of September. I began seeing immediate results days after I began implementing the strategy. The first change that I saw was in the attitude of my low-confidence/low-performing student. He began to show increased interest in what we were learning and also began participating in more whole group class discussions. The second change that I noticed was this student's quality of work. His usual "good enough"/"done" attitude slowly began to disappear. I began to notice that the work he was passing in was not only complete, but done with a great deal of care and thought. Instead of giving him a simple "Wow!" or "Great Job!" I took him aside and gave him focused and specific feedback. My student responded so positively from the focused feedback that I immediately realized that I needed to make this change with every student in my class!

What I learned from the experience and intend to try next:

This experience taught me that feedback can be a powerful tool when it is utilized the right way. Positive feedback is useless unless students know exactly how to use that feedback to improve their performance. "Good students listen to and look carefully at the feedback they get from teachers and use it to improve their performance" (p. 301 The Skillful Teacher). I believe that this quote holds greater meaning now that I have observed first hand the power of useful feedback and how it can dramatically alter the way students view not only their work, but themselves as well. I plan to continue using useful/focused feedback with my kindergarten students as well as other attribution retraining strategies.

It's Never Too Early - Kindergarten

Introduction

Part of my job as staff developer is to support the Kindergarten teachers as they implement a new, more rigorous assessment program and curriculum. I have helped administer some assessments and also taught the class as a whole. As I administered a writing vocabulary assessment to Sean, his first words were, “I don’t like to write. I can read, but can’t write very well.” This sounded familiar. The year before I had Sean’s older brother in my third grade class. Sean’s brother was also an above average reader with messy handwriting and an aversion to written tasks.

When I asked Sean to write all the words he knew, he could barely write his name. This was a child who had a high level of vocabulary and could read on a first grade level. He exhibited poor fine motor control. This was also evident during other tasks like cutting, coloring, and gluing.

His teacher and I both noticed that he would avoid all fine motor tasks by going to the bathroom or transitioning to another area of the classroom. His teacher and I discussed how to best encourage Sean. If we put pressure on him to finish a difficult task, he would often break down. From our experiences with his older brother, we knew that if not carefully guided Sean could experience confidence issues similar to his older brother. We discussed ways to boost his confidence while maintaining the high standards of the curriculum, including:

- Strategy One: Giving help when beginning a task

- Strategy Two: Recognizing superior performance

- Strategy Three: Conveying positive expectancy

Strategy One: Giving help when beginning a task

We noticed Sean often wandered from a task that involved lots of fine motor work. He tended to give up. His teacher and I discussed giving a lot of personal contact in the beginning of a task. She or I would set the expectation that he could accomplish the task, and we could also assess any material modifications that would increase his success. We would be sure to take advantage of “teachable moments” during and after the task to help Sean realize that effort yields success. We would not allow Sean to simply not finish a difficult task, but help guide him through it.

Reflection on Strategy One:

During one session, I helped the class make “color books”. They needed to cut up yellow pieces of paper and glue them onto an outline of a pear. Sean began saying, “I can’t do this.” I said, “Sure you can. Let me show you all a couple of different ways to make little yellow pieces. You can cut them or tear them like so.” He decided to tear them and successfully completed the task. When he finished the pear, I came by to recognize that he really worked hard and had a beautiful product. He eagerly began the next page of his book. An important part for Sean was catching him before he became discouraged. Letting him know I thought he could do it and sharing several strategies really worked for him. I addressed his table when offering strategies and that seemed not to isolate his weaknesses. His teacher shared with me that she also tried this approach and it has yielded success. We also discussed some potential pitfalls like dependence. She felt he needed this much support right now and that she would gradually release it as he became more comfortable.

Strategy Two: Recognizing Superior Performance

We discussed that one way to boost his confidence was to recognize the things he did really well like reading and using computers. We also discussed that this may present an opportunity to talk about how effort yields success. His teacher began by selecting a picture book to read about students in a primary class who each could do one thing really well. At the end of the story the main character discovers that he can use chopsticks better than the others because his family uses them daily. He begins to teach the others.

Reflections on Strategy Two:

Later when Sean was frustrated with a coloring task the teacher made reference to the idea that time was needed for skills to develop. He still remained frustrated because he wanted his project to look just like the teacher’s example and the work of the student next to him. His teacher recognized that it’s natural to compare yourself with others. I realize that she will need to show Sean how he is improving. I want to explore with her the idea of portfolios. In addition, Sean’s teacher shared with me that during computer lab she asked Sean to help a student with the computer. She explained to Sean that this student was not very comfortable with the computer yet, but since Sean had lots of experience he could help out. Sean brimmed with confidence as he helped another.

Strategy Three: Positive Expectancy

I asked Sean’s teacher what her expectations were for Sean’s writing this year. She said she expects all students to write their name “the kindergarten way” by the end of the year with a capital letter at the beginning and lower case letters following. She also expects them to attempt writing each other’s names and simple words. I asked her how she would modify this for Sean. She said she planned to talk to his occupational therapist to get some ideas for how to accommodate him. We talked about the idea of keeping your expectations high and not lowering standards. Sean’s OT suggested that he use a smaller pencil to help his grip and that the process of learning to write his name should be a progression of small successes.

Reflections on Strategy Three:

Sean’s teacher shared with the class how by the end of the year she expected all kids to write their name “the kindergarten way”. When Sean finished a paper she asked him to write just the first letter of his name using the modified pencil. She told him she knew writing was hard for him, but she would work with him to learn his name one letter at a time. They had the whole year to work on it. He agreed to write his first initial after she modeled it for him. When I worked with him later in the week, he told me he knew how to write the first letter in his name. He asked if I would write the rest. Sean’s teacher took the pressure of time off of him and set a clear expectation for the end of the year. I’m eager to see him write his name by next June.

Final Summary:

I learned a lot about myself as a teacher and coach from this project. As I worked with Sean’s teacher, I found myself falling into the habit of making suggestions that made things easier for the student. When working with Sean directly, I tended to lower my expectations so that he could feel successful and also selfishly so we could move one. I needed to remind myself that it didn’t matter if he missed one of his centers that day. He needed time to complete the project and my expectations had to remain high. We found that Sean became more willing to participate if we anticipated some of his frustrations and supplied strategies or modified materials. We also found out that Sean wanted his project to look like the others. He had high standards too and as teachers, we would have to help him reach those goals. We would also need to help him see his own growth and the results of his effort. I think his teacher will need to continue with the experiments we have tried. She will also need to have the goal in mind of gradual release of responsibility.

In addition, I learned that a student's confidence can begin to lower as early as kindergarten. Sean and others are already learning avoidance and giving up on certain tasks. It’s never too early for attribution training or retraining. As a staff developer, I learned that every teacher needs to examine his or her own belief system about what makes students smart. It’s difficult to share some of the realizations I’ve made about high expectations and standards if they haven’t made the journey themselves. My work as a staff developer must include having teachers examine their beliefs and expectations. As a classroom teacher and staff developer, I recognize the value of talking with another professional about your expectations for a child. Oftentimes I have been pointed in the right direction by another teacher who listened to my frustrations. The most important thing for me to do as a staff developer is actively listen. This will help me to understand their belief systems and work together with them to expand their repertoire of communicating, “What we’re doing is important. You can do it. And, I won’t give up on you.”

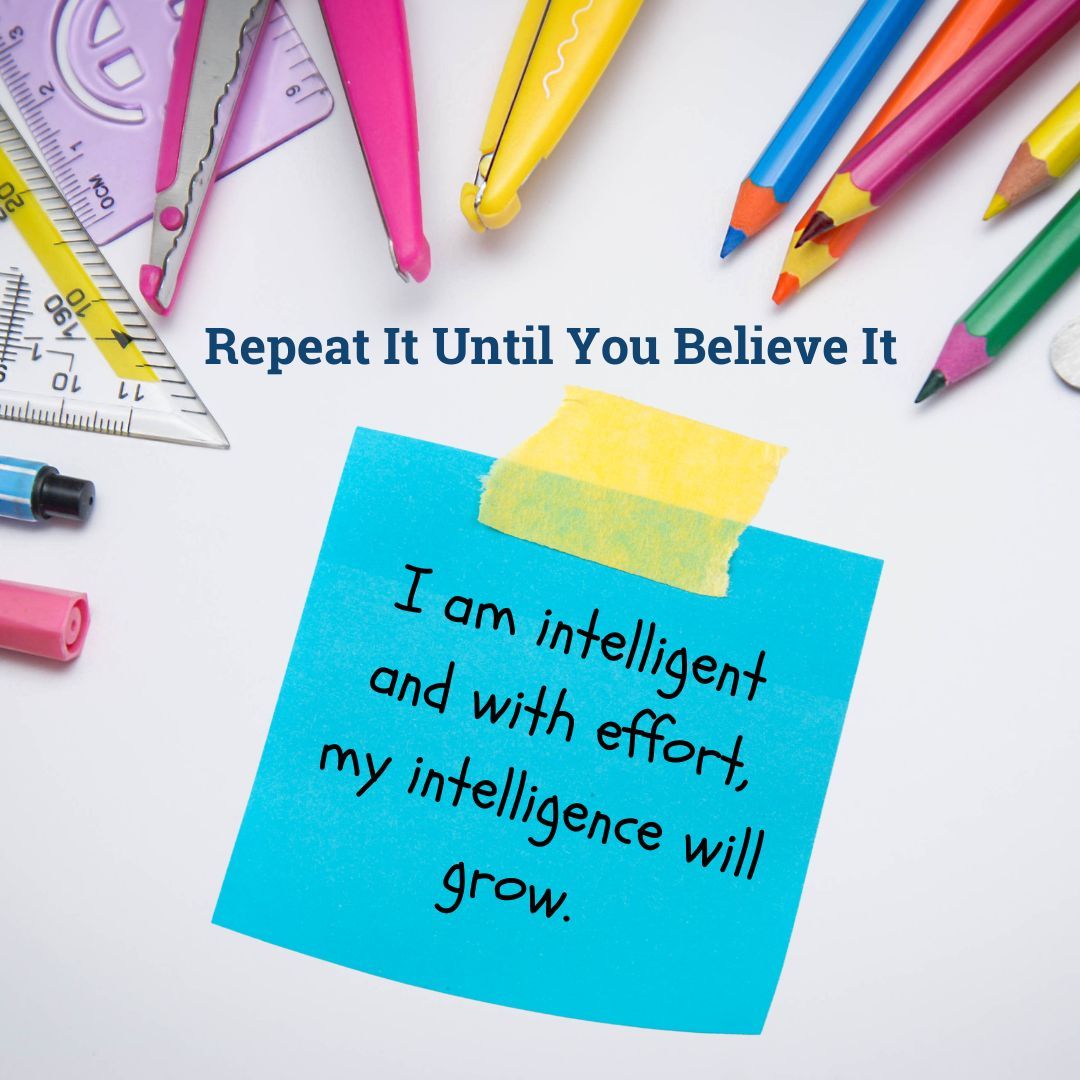

Repeat It Until You Believe It - Fifth Grade

The student I have chosen for this case study/experiment is a 5th grade male student. "W" came to our school this year from out of district. When he arrived in November, he was a low-achieving, low-confidence student. His test scores were low and he often did not do his homework. He worked very hard to remain invisible which at a small school like ours and in my class is an impossibility.

My student teacher and I quickly became aware of the problem that W did not believe that he was intelligent. He was convinced from his past school experience and grades that he was not one of the 'smart ones'. Because of this belief, he wasn't willing to invest time and effort in his schoolwork. In his words, "What's the point?"

When I told W that he was intelligent, he disagreed with me and strongly told me that I was wrong. I typed the following message and taped it to his desk:

I am intelligent and with effort, my intelligence will grow. |

W was annoyed when he first saw the message taped to his desk. He looked at me and rolled his eyes as if to say, “This teacher is crazy." I stopped by his desk and asked him to read the message to me. He refused because, “it's not true." So, I read it to him. We repeated this routine for two weeks daily, him refusing to read, me reading it to him and me making eye contact with a smile.

Little by little, I saw changes. When I first read it to him, he pretended not to listen. Then, he started to sit more quietly as I read. After a few days, he would smile when he saw me coming toward his desk at that time. Still he would not read it when I invited him to read it back to me. Finally, after two weeks, when I asked him to read it he responded, "Is it okay if I don't totally believe it?" To which, I responded, "I think that it's okay to not fully believe it at first. It's a starting point just to be able to say it.

During this same time, my principal took a special interest in W as well. At our school, the principal is always visible and involved with students, however, Mr. Larry made himself even more available to W. I let Mr. Larry know about good things that were happening in class so that he could ask about them in their conversations. During their conversations, W read his writing to Mr. Larry, showed him his Brazíl map made out of pinto beans, and he sought him out to share family news. He carried himself differently through the halls- the change was apparent as I saw him walking tall toward our classroom.

W's grades were improving as well. His average scores in reading and math were climbing. Still he did not credit his first weeks of better grades to his effort even as I reinforced that his effort made the difference. His family was now rewarding his hard work as he brought home better and better grades. He was asking how he did on tests rather than shrugging it off.

W's participation in math increased steadily. Although one mistake could still cause him to slump in the shoulders and retreat. I had to be very strategic in asking questions of him and others to demonstrate that missteps and false starts are part of learning, not a sign of inferior intelligence. Sometimes, I was more successful at this than others. This remains the hardest thing for W to accept. Intelligence does not mean I have all the answers all the time.

The changes in W have been dramatic, his weekly grades have improved, and he is putting more effort in schoolwork and homework. However, these ideas of innate intelligence die hard. W passed both his science and reading tests with flying colors on his first try. And yet, he merely shrugged when I smiled and pointed at the words on his desk. I have spent 6 months with W, and he almost believes me that effort grows intelligence. I think he believes it more than he lets me know.

How can we as a profession make sure no kids show up in 5th grade having already determined that they are not intelligent and therefore, school is not worth the effort? |

I am left wondering: How long will it take and how many teachers will have to tell W that he is intelligent before he truly believes it? What if he goes to middle school and no one tells him he is intelligent? What things happened to mold his self-image before I met him? In a culture where the idea of innate ability reigns, how can we as teachers educate the greater public to this new message? What if no one had ever told W this new idea of effort growing intelligence? How can we as a profession make sure no kids show up in 5th grade having already determined that they are not intelligent and therefore, school is not worth the effort?

Ta Da! It's All About The Effort - Middle School

Steven is new to our school this year. He stood out from the moment he walked into my class, late! He had a grown out mohawk that is two different colors, along with overgrown and very dirty fingernails. I was very curious to see how he was going to fit in with the other students.

The first few days of school I really focus a lot of time on creating a safe and welcoming environment for my class. We talk about the way we need to speak to and treat others, and discuss ways to make everyone feel safe and comfortable enough to learn and make mistakes. I really want to stress the importance of these things happening to ensure everyone's comfort.

The next things I noticed about Steve was that he called himself 'stupid” and “bad at school” in his written survey the kids fill out in the beginning of the year. I began to watch him more closely. I started to hear him calling himself stupid to other kids and eventually he said it to me.

Socially and academically, he was off to a rough start. He was getting picked on because of his hair and cleanliness by the other students. He reacted by swearing and name calling. Academically, he was struggling because he was putting almost no effort in any of his assignments and handwriting. His work was almost illegible. The subject for my case study was unfolding before my eyes.

My plan was to help him find a group of friends to help him feel less alone, and help him to see that he is not stupid, he is just not doing his best. At different points in the day, I have the kids work with different partners in class to help them to get to know one another a little better. Steve, who is a very nice and caring boy when he lets his guard down, was able to see that he had many things in common with other students. I noticed he was smiling more and having more laughs and fun throughout the day. Once he was feeling more secure socially, I began approaching him about his work. He had received several low grades and I knew it was because he was not trying. When I would discuss things in class with him, he was right on target during the lessons.

I reviewed his work and realized that he was not following any of the directions on his assignments. When he saw his grades his face dropped and he repeated to me that he was stupid. I handed him a highlighter and had him highlight the directions on the paper. I then had him look at his work and tell me what he noticed. He saw that he had not followed any of the directions and that was the reason for many of his errors. He also pointed out that it was hard to read his own writing! Ta-Da!

He told me it was because he slowed down and was taking his time and putting more effort in his work. |

We set two goals for that week. The first was for him to read and highlight all the directions on his assignments. The second was for him to try to keep his letters between the guidelines on the paper. Once he started to see how important it was for him to slow down and follow directions, the more confident he became in his work. At the end of the week, we met again to review his work. He received mostly 80's-100's on his assignments. I asked him how he could have done this if he was "stupid?” What things changed? Did my teaching change? Was the work easier? What happened? He said that he had changed! He told me it was because he slowed down and was taking his time and putting more effort in his work. I was so happy to see that he had made the connection to his improved grades and his effort.

We have bumps some days, but I just write the word effort on his paper when he has rushed and not done his best, and he will re-do the work. I have to do this less and less because he does not like getting loaded down with more work, when he doesn't do his best the first time. He answers questions confidently in class and he is very proud when he has mastered something. Working with him has changed his whole attitude towards school. He knows his effort is directly related to his success. He still needs to be prodded at times, but his work has improved tremendously. He was very proud of his progress report for one of the first times.

I have learned that it is a constant effort to help keep kids on the right track. I need to remind him about his effort and he responds positively. I know it will take time for it to become instinctual, but I think it is a habit that we all have to struggle with in our own lives as well.

It's Not About Luck - Middle School

Alex entered my classroom on the first day of school as a new student to our district. Well, almost new. Alex was at WMS in grade 5 two years ago. He then moved to a nearby town and attended school there, only to have been retained and having to repeat grade 6. Alex is a big thirteen year old in a class of smaller 10 and 11 year olds.

Since that first day, Alex has expressed several times that he was stupid and didn't know anything. Yet he also expressed to me that he couldn't wait to get to the high school so he could play football like his Dad. I saw that Alex put very little effort into any work that he did, but enjoyed participating in our class discussions. I thought that Alex would be an excellent student to use for attribution retraining.

During the first week of school I had given all of my students a survey. This survey included questions such as the reasons students do well or poorly on tests, the reasons they play well in sports, and who in their lives impacts their ability to do well in school.

Alex's responses included that he felt that the reason he does well or not on tests is because he was lucky or unlucky. CLASSIC! I also began to talk to my students about becoming smart and how that can happen to all of them. Alex was very vocal in telling me that there is no way he could be smart.

I tried talking to Alex privately to explain that I believed he could do well in school. I told him that whatever it takes, I would show him how to study, what to study, and why it's important to study. I used words like, "Putting in the effort will get you smart." and "I know you can do this, because I saw you solve a smaller problem yesterday. Let's put what you know together and solve this problem.” On Alex's papers I would put words like "Good effort” or “Put in more effort" on assignments that were not his best. It seemed to be working. Slowly Alex began to say things like “I get it" and "I can do this if I try."

Just a few words made the difference in Alex's life. He just needed to hear that someone believed in him and would show him how to get smart. |

Just a few words made the difference in Alex's life. He just needed to hear that someone believed in him and would show him how to get smart. Smart wasn't just something that other kids were. He could achieve that success also. I will continue to guide Alex through this school year showing him that he can do it if he puts the effort in. Last week Progress Reports were sent home and Alex told me that his parents were surprised at his good grades. He said he told them that he is smart and can get good grades. This project made me realize that I can impact a student's life tremendously.

Accentuate The Positive - Middle School

Mrs. L, a veteran teacher, came to me in mid-September. She told me she was sorry she had ever told our principal that she wanted a change and a challenge in her teaching assignment. After teaching 6th grade English for years, the principal had assigned Mrs. L two classes of 8th graders who seemed destined to fail the Maryland Writing Test (The MWT is an assessment of functional writing skills, the passing of which is a requirement for graduation in the state of Maryland. ) Mrs. L had until November to prepare these 8th graders for the test. By the end of the first day of class, she knew that her task was going to be a greater challenge than she had anticipated. The students in her two writing classes took one look at the others in the class and knew immediately that the class was a remedial class for dummies. “How can I convince these kids that they are capable of passing the test?” she wailed. I realized that I had found a perfect situation for my Expectations Case Study.

How can I convince these kids that they are capable of passing the test? |

Although Mrs. L and I could easily have chosen any student from either of her classes as a subject for the case study, we picked K from 7th period. Mrs. L was able to tell me that informal reading assessments from Spring 2000 showed K reading at a 5th grade level. Her criterion reference test scores from last spring for Reading/Language Arts indicated that her performance was slightly below standard.

Mrs. L reported that K had been turning in very little work in the Test Prep class and what had been turned in was of low quality. She came late to class and looked for ways to escape. She wouldn’t bring the materials she needed for class, wouldn’t stay in her seat, and wouldn’t stay on task – all behaviors that would indicate K has very little self-confidence in her ability as a learner. K often created situations that ensured that Mrs. L would have to focus on her poor behavior rather than her academic performance. K would occasionally produce work when she was sent to the in-school suspension room, but there seemed to be no way to get her to make much effort in class.

I was surprised to hear Mrs. L describe K’s antics in her class and later to see them for myself. I remembered K as a sixth grader, and though I didn’t know her well, I knew enough about her past history to recognize that both her academic performance and behavior were in sharp decline. As a 6th grader, she had been eager to participate in all learning activities, especially enjoying those of a cooperative nature. She had a sunny temperament and was willing to try new things to please her teachers. I remembered reading about students who stop liking school and begin avoiding academic challenges after reaching middle school and wondered if K was a case in point. Mrs. L and I agreed that unless we could reach this student, she would surely fail the Maryland Writing Test as well as the Test Prep class.

I think you espect [sic] us to act dumb because you don’t think we know how to write. |

Experiment 1: Communicating an Essential Belief

Since the students in Mrs. L’s Test Prep classes believed that they were placed in her class because they had little ability, I wondered what Mrs. L believed about her Test Prep students. If she, too, thought they had little chance to pass the Maryland Writing Test, the class was doomed. So I asked her to actively read, as I had done, the chapter on expectations in The Skillful Teacher. We then shared what we thought were the essential points and interesting details. Mrs. L told me that she really did believe that all students in her class could pass the writing test if only she could get them to work at it. We decided to test whether or not Mrs. L had clearly communicated “You can do it!” attitude to her students. The following day, in place of the regular warm-up activity, Mrs. L asked her class to write down what they thought her expectations were for them and what they thought it would take to pass the Maryland Writing Test. The results were a real eye-opener.

Reflection on Experiment 1:

To the first question K responded, “I think you espect [sic] us to act dumb because you don’t think we know how to write.” To the second she replied, “I could pass the test if they ask me to write about something I know or if we have practised [sic] writing the prompt in class.” These responses were similar to those given by others in the class. Most thought Mrs. L believed them to be incapable of becoming good writers. Like K, a few who thought they had a chance to pass the writing test attributed passing to luck. Most believed they could never pass it.

Mrs. L was appalled by the responses and at the beginning of the next class spent 20 minutes focusing on the positive – all the good writing skills the group already possessed. She told them that there was plenty of time for them to acquire those skills they still needed to pass the test. All they needed to do was to put forth a little effort. “I know you can all do it!” she repeated again and again. That day, more was accomplished in the class than on any previous day, Mrs. L reported, even though the first 20 minutes of class was spent in discussions. Even K turned in a couple of paragraphs at the end of the class!

She told Mrs. L that it was easier to work on getting one thing right than to try to keep “everything I’m supposed to do right in my mind.” |

Experiment 2: Setting Goals

Mrs. L was pleased with her initial efforts at more clearly communicating the “You can do it!” message to students and didn’t want to lose momentum. We agreed that she would take the written work that students had turned in the previous class and use that as a baseline assessment from which students could set specific learning goals for themselves. Mrs. L constructed a series of posters that outlined specific skills students needed to pass the test. She then marked the class papers identifying which skills individuals showed mastery of and which they still needed to practice. She also developed a chart that students could use to list the skills they had already mastered and to keep track of the ones they needed to work on.

Reflection on Experiment 2:

At the beginning of the next class, Mrs. L had students list the skills they had already mastered on one side of their charts and pick just one skill that they would like to master next. Mrs. L reported back to me that students were comparing lists with one another and boasting about the skills they had already mastered. Better yet, she heard the beginning of cooperation among the students. She overheard one student saying to K, “Oh, that’s easy. I can show you how to do that.” K had chosen to work on the skill of writing an introduction that incorporates words directly from the prompt. Although she wasn’t willing to let Mrs. L work with her, K did allow the student who had said she could show K how to write an introduction to sit with her. Together the two girls wrote introductions to three different prompts. When Mrs. L spoke to K near the end of the class, K seemed pleased with her own work. She told Mrs. L that it was easier to work on getting one thing right than to try to keep “everything I’m supposed to do right in my mind.” I’d say that the strategy of having K focus on one small, but attainable goal was a good match between learner and strategy.

I think that after saying, “You can do it!” so many times to her class, she now truly believes it too! |

Experiment 3: Providing Detailed Feedback

Mrs. L says she no longer dreads 7th period. I think that after saying, “You can do it!” so many times to her class, she now truly believes it too! Yet of all the students in the class, she feels she made the least progress with K who is still reluctant to let Mrs. L work with her. Since building a personal relationship with some students is a long process, I encouraged Mrs. L not to give up on K. I proposed that she begin to work on the type of feedback she gives to her students, making the feedback more detailed and having it focus on skills performed well, in addition to providing specific guidelines on how to improve those areas where further efforts were still needed. Also, rather than just handing back papers with feedback to students, I counseled her to set up in-class appointments with students to discuss their efforts.

Reflection on Experiment 3:

Two weeks ago, in-class conferences would have been impossible because much of Mrs. L’s time was spent in dealing with inappropriate behaviors and complaining students. Now when I visit 7th period, students are on task most of the time – they are still 8th grade students after all – and the class climate seems much more positive. Students know that when they sit down with Mrs. L that they will hear about what they have done right as well as what they still need to work on. K still needs to be redirected more often than others, but she is producing more work and that work is of a higher quality. She now allows Mrs. L to sit down next to her and discuss her work and for the first time, I observed her going over to ask Mrs. L a question about her work. K has added writing introductions to her list of mastered skills and is now working on supporting her opinions with details and examples.

She told me that she sensed that students began to perceive her as more of a guide than “the enemy” when her feedback included positive comments as well as specific steps they could take to improve the skills they were trying to hone. |

Final Reflections

Mrs. L sat down with me to reflect on our 3 experiments. Although for the purpose of this assignment, I focused on the performance of one student, K, Mrs. L had originally come to me for help with the whole class. Because all of the students in her Test Prep class were low confidence learners, the strategies we selected were chosen to benefit all in the class, not just K.

Mrs. L said that when (not if!) she teaches this class again, she will begin with a baseline assessment of her students’ writing skills which she will use to help them set small, attainable goals for their own learning. She said that once she did that with her 7th period, students began to see the task of passing the Maryland Writing Test as achievable. She felt that students responded well to more direct feedback from her and that she would continue to discuss that feedback personally with students. She told me that she sensed that students began to perceive her as more of a guide than “the enemy” when her feedback included positive comments as well as specific steps they could take to improve the skills they were trying to hone.

Until I broke the task down into different skills that they were able to master one at a time, passing the writing test must have seemed like a hopeless task to them. |

Finally, Mrs. L said that she hoped never again to have to ask students to write down what they thought her expectations were for them and what they thought it would take to pass the Maryland Writing Test. She hoped to communicate her expectations for them so clearly and so frequently that that particular experiment would never have to be repeated. She believed that the mistake she had made with her Test Prep classes was in communicating the importance of passing the test without clearly communicating that she thought they were all capable of passing it. And to make matters worse, she told me, “Until I broke the task down into different skills that they were able to master one at a time, passing the writing test must have seemed like a hopeless task to them.”

"Little Things Make a Big Difference" - High School

Step One:

Select a student whose academic performance is not meeting your standards and whose behaviors signal that she has low confidence as a learner.

I have had the pleasure of working fairly closely and regularly with several teachers and students at my residency site this year. For my expectations case study, I selected a more experienced teacher and one of my own advisees to collaborate with. Let’s place this case study in context. Please also note that the actual names of every person and place have been changed to preserve the confidentiality of the subjects.

The Setting:

My residency site, Village High School, is a relatively small school (490 students) , located in the heart of a big city. The physical and philosophical contexts of the case study are absolutely critical variables for the reader to grasp as he or she reads along. Since this high school is physically located on a college campus, many of the typical markers and structures which define high school life have been abandoned. The school does not utilize a bell system to mark time and students are free to visit any part of the campus – hopefully to access the many resources offered by the college including the library, gymnasium, dining facilities, and art studios. The school’s relatively small size and emphasis on alternative assessment tools (portfolios) has created many formal and informal opportunities for student-teacher collaboration.

The Profiles

The student I chose to profile, Maria, is a fifteen year old, second year Latina student at Village that also happens to be one of my advisees. She can often be found socializing with friends and acquaintances either in the school’s roomy cafeteria or directly outside of the school – a public space that the adult community has ceded to the students. Although Maria often “cuts” her classes and is reluctant to complete most of her major assignments on time, she manages to eke out passing grades. As one of her advisers this year, I have frequently caucused with Maria and her mother to discuss her under-performance this past year.

It is impossible to discuss the student without also offering a similarly brief profile of the teacher cooperating in this case study. Maria has had a particularly difficult time regularly attending her first period social studies class that begins at 8:00 a.m. every morning. Her teacher, Ron, has taught at Village for thirteen years and continues to devote long hours to the craft of teaching. While there is no question about his dedication to the school, I have observed what I would describe as a weak bedside manner with parents and students. Ron’s comments can often appear insensitive and his teaching style is quite didactic. Most tellingly, you rarely see any students loitering around his professional space within the teacher’s ante-room unless they are receiving formal feedback on work. Consequently, Ron is unable to rely on his relationships with students to leverage improved academic performance and achievement from them.

Goals for the Expectation Case Study

Ron is not an unsatisfactory teacher, just a flawed one as far as his relations with students is concerned. And Maria is not a failing student – she is presently underperforming. My two goals for this case study were:

- Help Maria (a) acquire the confidence to meet very specific behavioral and academic expectations, and (b) negotiate or circumvent her “personal dislike” of Ron.

- Help Ron align his promises, practices and results. Ron believes he wants to assist every one of his students, yet his insensitivity and unwillingness to go the extra mile for particularly reluctant readers and writers like Maria often translates into lower academic expectations.

When I inform him that I wish to help inspire Maria to recognize her strengths and excel in class, Ron simply replied, “Good luck!” |

Journal One: Establishing and Enforcing Behavioral Expectations

Ron has somewhat reluctantly agreed to assist me with my expectations case study. Although he is an experienced and somewhat respected faculty member, I suspect Ron is acutely aware of some of his pedagogical shortcomings. Thankfully, our friendship wins out and he agrees to participate when I inform him that I wish to help inspire Maria to recognize her strengths and excel in class. Ron simply replied, “Good luck!”

Maria is chronically late for Ron’s first period. After speaking with Maria and her mom independently, I learned that she gets up at 5:30 a.m. and leaves the house shortly after 7 a.m. Maria’s commute is relatively short (35 minutes), so there must be something else preventing her from arriving on time, if at all. I sat Maria down in my office and learned she “doesn’t like” Ron. I pressed further and she reveals that Ron is “always on her back” and “never gives her any credit” for the work she performs in and out of class. I sympathize with Maria, but in the same breath remind her that she has an obligation to pass Ron’s class in order to graduate and must overcome her personal likes and dislikes of individual teachers. She reluctantly agrees to give Ron’s class a chance.

The very next day I visited Ron’s first period class and discovered Maria was nowhere to be found. I also quickly learned that Maria is not the only student chronically late. My student sources informed me that Maria was socializing in the university’s gymnasium across the street from the high school. I darted across to the gym, retrieved an embarrassed and increasingly more reluctant Maria, and escorted her to Ron’s class. On the trip over, Maria asked, “Why are you following me?” revealing that she was not accustomed to having an adult at school invest much time checking on her attendance. Recognizing this opportunity, I immediately responded, “You know you could excel in Ron’s class if you applied yourself. Why don’t you show everyone else?” I also added, “This will not be the last time I check on your first period attendance myself.” Maria smirked, walked into Ron’s class, and slid into the nearest seat.

The following day I peeked into Ron’s class early into first period and was pleasantly surprised to find Maria in class. She smiled when she saw me in the doorway but I continued on my way nonchalantly. At the close of the period, I entered the class and asked Maria to sit with me and Ron for a moment. Of course, I asked both, “How did things go today?” Maria replied, “OK.” Ron was not so reserved or optimistic. He immediately pointed out that Maria spent most of the class moisturizing her hands with hand cream. Maria immediately retorted, “I was listening to every word you said!” Ron was absolutely correct to point out Maria’s lack of productivity for the entire class period, yet again, he missed an opportunity to connect with Maria. It turns out Maria was one of seven students to arrive to class on time while the remaining two-thirds of the class trickled in late. Ron failed to acknowledge this small but incredibly important demonstration of effort on Maria’s part. Ron eventually did recognize this effort at the close of our brief conversation with Maria, but not without some prodding.

Reflection:

Village High School articulates a desire to construct a community of commitment in which adults and students regularly collaborate, communicate openly and freely, and assume responsibility for each other’s learning, although I’m not sure every adult possesses the interpersonal tools to make that happen. Ron clearly needs to work on his choice of words, his clarity (of expectations), and willingness to appreciate and acknowledge student progress no matter how incremental. Maria still needs to work on getting to class on time.

Journal Two: Building Student Participation in Class

Maria has begun attending Ron’s first period regularly with some prodding by her mom and me. She still is unwilling to engage Ron in unmediated, extended conversations because she believes “he does not like her.” I still suspect her allegations are not that far off, but we continue on for both their good.

Ron is a relatively strict, but inconsistent disciplinarian in class. Characteristics of his inconsistency include: unclear expectations, inconsistent follow through, and no “recognition of responsible behavior.” Maria could help Ron by articulating her questions or confusions about expectations, directions, and activities. Until now, Maria has chosen to withdraw. Ron has recognized this tendency himself and with some coaching outside-of-class has agreed to try and re-focus Maria’s attention back to class by inviting her to lead parts of group activities and simply checking on her progress periodically before, during, and after class.

Reflection:

Ron seems to be devoting more time and care to reiterating his behavioral and academic expectations for class and supporting Maria’s progress with positive verbal interventions and constructive one-on-one consultations during class. My ten-minute walkthrough the following day confirmed my assessment of the situation. Maria clearly appeared more engaged and interested in class than earlier in the week. She still needs to work on seeking assistance when she is unclear, confused, or lost. Maria also needs to demonstrate whatever mastery of the material she does possess by participating in class.

More importantly, Ron discovered that the structure created more opportunities for him to support and encourage struggling students like Maria in class. Maria also conceded her appreciation for the structure and found herself staying on task far more often. |

Journal 3: Routines and the BBC

Maria admitted skipping class when I greeted her later in the day (Friday). She didn’t have a viable excuse, nor did she offer one. Ron was clearly disappointed, though not surprised. I spent a solid twenty minutes bolstering him up, reminding him of the progress he has made with Maria and strongly encouraging him to continue with his efforts.

Ron is fairly traditional compared to most of his colleagues at Village High School. Students sit in pre-assigned seats in rows and are strongly discouraged from collaborating with those alongside them unless explicitly given permission to do so. At times, this structure works in Ron’s favor and the class is quite productive over the seventy-minute period. Other times, the class seems stifling. Ironically, Ron has not established many class routines, other than taking attendance after the first ten minutes of class. As a result, students like Maria that miss a day or two have difficulty re-connecting with the class. Ron understood the students’ dilemma, though remained unsympathetic. I then reminded him of our commitment to every student’s success and obligation to create as many opportunities for each to achieve despite the choices they make.

I introduced Ron to the Blackboard Configuration (BBC) many schools have found successful. I asked Ron to place the class’s learning objective, essential questions, agenda, reading assignment, and homework on the blackboard each day in the same place for a week and then assess his student’s performance. The results were readily apparent in the first three days of our experiment. Students were not only copying the BBC into their notebooks, but holding Ron to the agenda and learning objective he put in place. Although she continued to arrive to class on time, Maria remained easily distracted and continued distracting her peers. Ron found his job became much easier after he discovered he could subtly approach any student off task and direct them to the agenda. More importantly, Ron discovered that the structure created more opportunities for him to support and encourage struggling students like Maria in class. Maria also conceded her appreciation for the structure and found herself staying on task far more often.

Reflection:

I was pleased that I was able to play to Ron’s strengths and assist Maria’s learning in class. My professional relationship with Ron also seems to be improving now that we have witnessed some success with Maria and he realizes I am not siding with her. My relationship with Maria also continues to improve now that she recognizes that she can excel in Ron’s class and I am not “just out to get her.”

Journal Four: Personal Relationship Building

Part of the root of Ron’s difficulties is the lack of a personal relationship with Maria and his other students. Maria perceives Ron to be cold, unfair and unsympathetic to her “problems.” Ron’s actions, both in and out of class often confirm this incomplete view of Ron. As a result, Maria found herself cutting or shutting down in class altogether. The introduction of the BBC and a greater effort to support and appropriately praise Maria has helped considerably. Maria’s attendance and productivity have improved dramatically. How does Ron build on the success of the last three weeks?

Village is somewhat unique in that none of the teachers are assigned to a particular classroom. Instead, each teacher is provided with a moderately sized cubicle with room to consult with students. I suggested that Ron establish both formal and informal office hours at his cubicle. Students can either sign up for assistance or simply drop by with a question. Ron embraced this suggestion immediately. Regrettably, Maria did not take Ron up on his generous offer during this expectations case despite my gentle reminders. Several other struggling and highly proficient students began to take advantage of this extra, highly-personalized time with Ron.

Gladwell contends that “little things can make a big difference.” Starting epidemics, trends, or movements, for example, requires concentrating resources on a few key areas. |

Final Reflection

This expectations case study with Maria and Ron reminded me of a phenomenon Macolm Gladwell describes in his recent best seller, The Tipping Point. Gladwell contends that “little things can make a big difference.” Starting epidemics, trends, or movements, for example, requires concentrating resources on a few key areas. Twenty-five percent of the students registered for Ron’s social studies class were regularly absent or excessively late (20 minutes or more). Rather than simply write these students off, Ron needed strategies for bringing these students back to class. I chose to collaborate with Maria because she does not fit any stereotypical profile of a student “at-risk”. Her mother is an active and positive presence in her life and Maria entered the class reading and writing on or above grade level. Yet, she was regularly cutting class and only producing enough work to pass.

Gradually, both Maria and Ron took proactive steps toward improving their relationship, improving their quality of the work, and most importantly, deconstructing stereotypes they firmly held. Maria began to improve her poor first - period attendance and negotiate her personal dislike of Ron with consistent counseling, support and encouragement. Moreover, as Maria’s confidence and comfort in class increased, she began to exert effective effort and excel academically despite her unfounded belief “Ron was picking on her “ and “she wasn’t any good in social studies.”

Maria never did relinquish her dislike for Ron. Perhaps, that wasn’t the point of the exercise. Maria, like many students, benefits from consistent, constructive and honest verbal and written assessments of her progress and behavior to succeed. The importance of caring relationships within a school community has already been well documented and reinforced by this case study. Deborah Meir, for example, writes, “…close teacher-student relationships allow teachers to demand more of students without being insensitive or humiliating.” Equally important Maria and I noticed an improvement in Ron’s classroom performance. His expectations of students became far clearer, his classroom acquired some student-friendly structure and he became less parsimonious with his support, praise, and time.

Not one of these alterations in style, behavior, or practice made by either Maria or Ron was particularly extreme, experimental, or cutting-edge. Yet, each made a substantial difference in the overall performance of the entire class. |

Not one of these alterations in style, behavior, or practice made by either Maria or Ron was particularly extreme, experimental, or cutting-edge. Yet, each made a substantial difference in the overall performance of the entire class – a result that far exceeded my own expectations for this case study. Cutting in Ron’s first period class declined by fifty percent, the tone of the class became less adversarial, and the quality of student work submitted rose dramatically.

Breaking Down Barriers - High School

Introduction:

I worked on this case study with Mr. S, the same teacher with whom I did the mastery case study. Mr. S is in his second year of teaching, and his job is split between teaching math and technology. He and I co-taught a class last spring, and in many ways he sees me as a mentor. For this project Mr. S selected J, a student in his second year math class. J is a 9th grader in a predominantly 10th grade curriculum.

At times, Mr. S has wondered if she was misplaced, but her previous performance in math – both on test scores and report cards – indicates she was not. Still, her lack of belief in herself has held her back, and he thinks that she may have developed more math esteem in the first-year curriculum. While that may have been true, I worked to persuade Mr. S. that J was where she should be and it was up to us to help her grow accordingly.

Other teachers have also struggled with J, and in one case the teacher has essentially given up on her, resulting in her quitting the class in return. On several occasions, she’s been sent to the office for “sleeping” in this teacher’s class, which I interpret to be her defense mechanism against the teacher’s treatment. Mr. S remains committed to helping her succeed.

My observation of J in class confirmed the traits Mr. S described in our pre-observation meeting. She spent the warm-up part of the class fixing her hair and preening in a mirror. Then, during guided work, she raised her hand incessantly. By my calculations, Mr. S spent 6 of his 20 minutes in this part of the period tending to J which left the other 20 students minimal access to him. Her ability to rope him into helping her was masterful. Her normal move of calling his name while raising the hand was standard. Her ability to engage him from across the room, however, was impressive. In my post-observation meeting with Mr. S, I shared my view of J’s behavior. He had no idea she was monopolizing his time that much, and he was clearly concerned. But he also felt that he allowed such indulgences because he wants J to know that he cares, and he doesn’t want to send signals that he’s given up on her. We agreed that the two aren’t mutually exclusive and that there were some next steps he could take. I also gave him three chapters from Fred Jones’ Tools for Teaching to read. They focus on weaning the hand raisers and providing audio and visual cues to help scaffold students’ learning.

First Phase:

Mr. S and I discussed how he could approach the situation with J in their next class. First, I recommended that he be over- positive in his interactions with her. By using the mantra, “This is important – You can do it – I won’t give up on you, “ he could help her get at her lack of math esteem. He was already living the mantra; now it was time to verbalize it to her.

Secondly, we discussed Jones’ chapters and identified strategies from them to help wean J of her hand raising addiction. Mr. S felt that he could do a better job of only providing J with cues to the next step of a math problem, instead of getting suckered into completing the problem for her. He was most concerned with how she would react to him refusing to help her when she had a question. We discussed at great length the best strategy for a transition. Fearing that she would shut down if it just happened all of a sudden, we added an element to his overall plan. Students were going to be working in groups on a particularly challenging word problem. In order to direct the focus on having them help each other, he was going to announce that each group would only get 2 consultations, one written and one spoken. Additionally, he decided to rearrange J’s group so that she had more collaborative partners. In this way, she wouldn’t be able to rely on Mr. S in a way that didn’t isolate her situation.

Second Phase:

In our next meeting, Mr. S reported that J had done well, though the class hadn’t followed his script as he’d hoped. The do-now activity ended up taking more time than anticipated, so the group component was reconfigured to be an individual task. Students were asked to read through the problem and write down conceptually the steps they would need to take without plugging in numbers. J was one of the first to raise her hands and Mr. S says he made a conscious effort to provide her with only the essential information. He felt that it had worked well and was encouraged.

We discussed additional steps that could be taken. In looking over the homework he was going to assign, he noted that in the sample problem he had included each step, as suggested in the Jones book. When I asked him if J would understand it all, he admitted that he didn’t think so. We then talked about what additional information she would need and agreed that annotating the steps would help considerably. He also planned to continue the group work problem and would institute the “consultation” rule.

Third Phase

We met again after the next class. Mr. S was excited to report that the group work had gone well. J had followed directions and had worked especially well with her team. In one instance, she started asking Mr. S a question, and he asked the group if it was their official consultation. They quickly said no and returned to the work at hand. Also, she had gotten a 4 out of 5 on her homework.

I also asked him how he was doing with the mantra. Interestingly, his answer launched us into a complex discussion about classroom management and Mr. S’s relationship with his students. He feels that kids like him because he’s young and fun and he makes math enjoyable. But he is also frustrated that they take advantage of his kindness. In this instance, he was disappointed that J’s friends didn’t take the mantra more seriously. Instead, they tried to use it as a chance to get him off topic and engage in lengthy philosophical discussions. They asked questions such as, “Why is this important, Mr. S?” and “So if you won’t give up on me, does that mean you won’t fail me in the class?” He took the bait and responded with long, careful answers. Ten minutes later, he found himself talking in circles with only a few kids, while the others dozed off or did other homework. I promised him that he could find the balance between making math fun and still running a tight ship, but that it was hard work and that he would have to be willing to make changes, both in his curriculum development and his personal demeanor. We agree to return to this topic early and often.

As far as J was concerned, we agreed that the next step was for him to discuss the situation with her directly. At this session he would need to be supportive but honest. First, he would need to convey the mantra in his own words, while providing examples from the year to remind her that she really could do it. He would then need to share with her 6 out of 20 minutes data point and use that as an example of a broader dependence. Finally, he would identify the most recent group work as an example of her ability to not rely on Mr. S for all the answers.

This was a fantastic project. At first I was concerned that it would be far too time consuming and possibly too limited in scope to help on a broad enough scale. I was wrong on both counts. |

Final Reflections

This was a fantastic project. At first I was concerned that it would be far too time consuming and possibly too limited in scope to help on a broad enough scale. I was wrong on both counts. First, the time commitment was minimal. Mr. S and I had six conversations about J, and only two lasted more than 5 minutes. The long ones were excellent discussions about broader pedagogical issues and I think helped Mr. S grow as a practitioner. The other 4 were quick updates that included facts about what happened with J and idea swapping about next steps. Secondly, our discussions about J were certainly about her, but her issues pertained to other students as well. Furthermore, by searching for solutions to help J, Mr. S was adding to his tool kit a whole host of strategies for helping all his students.

By searching for solutions to help J, Mr. S was adding to his tool kit a whole host of strategies for helping all his students. |

Of course, I also felt limitations. Isolating J’s situation from the rest of the class was difficult to do. Getting her fully weaned from unnecessary hand raising is a tremendous challenge, since it’s a behavior she’s developed through years of training. On its own, perhaps the problem could be addressed more directly. However, in a classroom where another ten students have different issues of similar impact, Mr. S must pick and choose his battles. Additionally, since attribution retraining takes time, it’s yet uncertain how j will turn out.

Regardless of J, though, Mr. S benefited tremendously from this project. He is a better teacher as a result, and I am a better supervisor. I will most certainly use this strategy again. It focused my efforts with Mr. S so that he and I both were thinking in small incremental steps while still making large gains in his ability. It also kept our energies centered on what was best for J, which is a powerful way of connecting teacher development to student achievement.