To See the Soul of a School, Look at Common Planning Time

There are three big ideas in this article, and they are interdependent.

First: Error analysis, and then planning and delivering re-teaching are key practices in schools that get extraordinary results for students. Analyzing student errors and planning to re-teach content in new ways to those who have not yet mastered it is a critical act if we want to improve student achievement. Ideally each of us would learn to do this in the flow of making daily lesson plans. Group error analysis and planning for re-teaching by teachers who teach the same content is a high-leverage (if not the highest leverage) team practice. It maximizes the impact of this work and should be a number one activity teams spend time on in their meetings.

Second: School leaders must prioritize having teams spend time on error analysis as well ensure that that the analysis is translating into revised and better teaching practice. Without the principal making these practices a priority, they may not happen.

Third: A school leader alone cannot ensure this process is successful. The leader needs a team committed to the vision of making this a shared practice throughout the school who will assist teams to function this way. This work can only be successful if there is a strong adult professional culture where adults trust and support working together. (See Adult Professional-Draft Chapter)

The first part of this article will make the case for group error analysis and explain what it means. The second part will take on how leaders lead to make it happen.

Error Analysis and Teams That Do It Well

One of the highest leverage activities found in schools that raise student achievement is to run a meeting where the team does the following:

- Lay out student work – either the results of yesterday's class work or the item analysis of an interim assessment.

- Identify where students are struggling and which students did the struggling.

- Try to figure out what the students might have been thinking to make the errors.

- What are our hypotheses?

- How can we find out which of these hypotheses is true?

- Use those insights to design re-teaching lessons for those who need it.

- What different teaching strategies could we use to “fix” or undo whatever led to this error and help students solidify their skills and concepts?

- How are each of us going to plan and manage time and tasks in class so that we’ll get fifteen minutes (or whatever it takes) to re-teach the skills and concepts. [Target: at least 2 times a week for groups of students who don’t have it.]

- How can the team help? Determine whether there is a way to share knowledge, skill, or students to benefit both students and colleagues.

Item Analysis

Imagine the following:

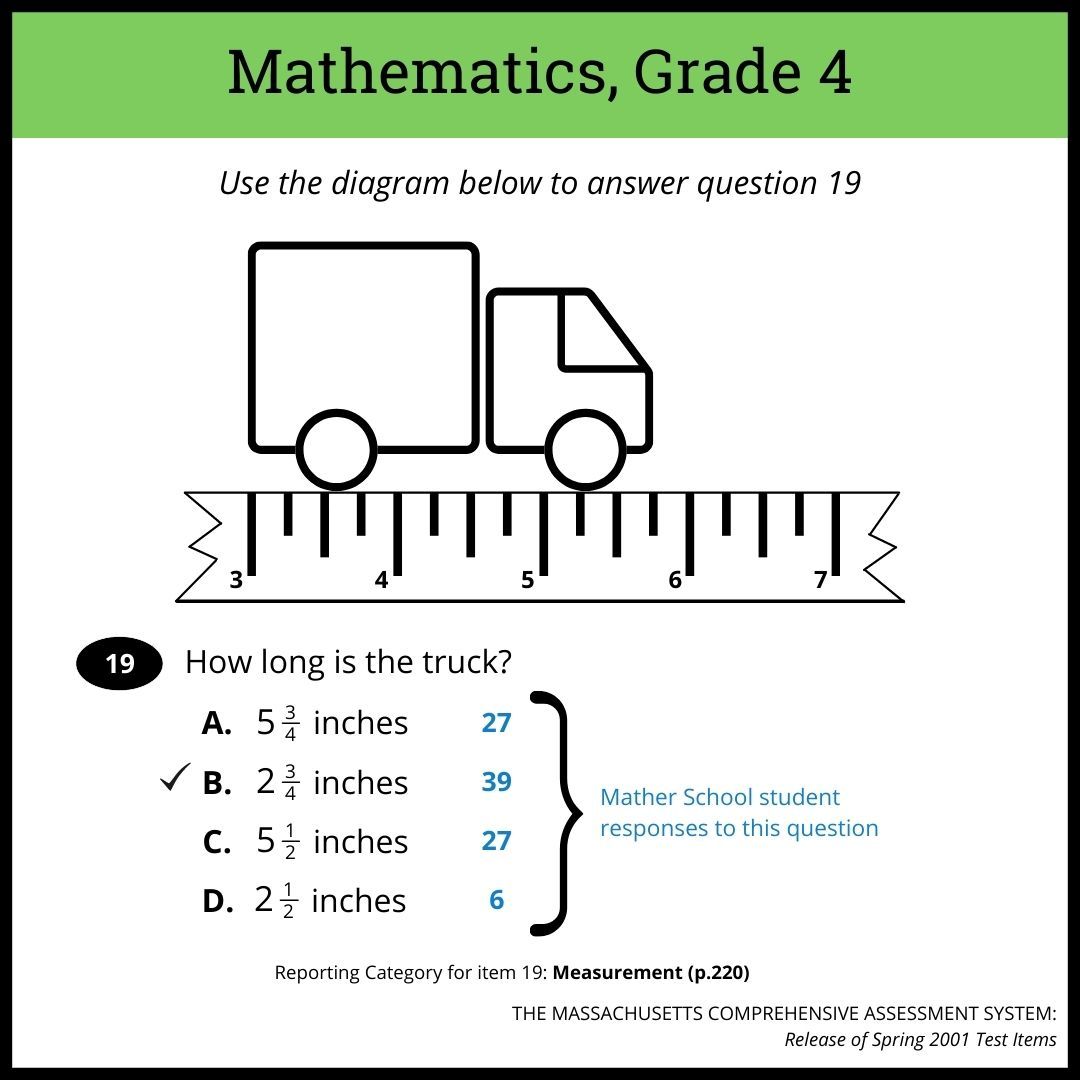

During their Common Planning Time at 11:10 AM, four fourth grade teachers are looking at the item analysis below from an interim assessment. It shows the test item and the data on how ninety-nine students responded. Thirty-nine students had the correct answer (B) and sixty didn’t. The tally was generated by Kim Marshall, at the time principal of the Mather Elementary School in Boston.

Figure 1. Fourth-Grade Mathematics Question

Here is the teacher dialogue while trying to identify what students might have been thinking when making an error.

- Teacher A: Twenty-seven students incorrectly chose answer C. What might they have been thinking to pick that one?

- Teacher B: Perhaps they did not know that they need to “zero” a linear object on a ruler when measuring its length. I find this is quite common in elementary kids. And rulers don’t help, since many of them place the first hash marks a quarter inch inward from the physical edge of the ruler.

- Teacher A: …or maybe it’s about creating an imaginary zero at any point on the ruler, but then counting up in inch units to the end of the object.

- Teacher C: So maybe the problem is the children don’t know they have to put the beginning of the object at the exact zero point on the ruler and that zero point might not be the physical left end-point of the ruler.

- Teacher A: Oh, I don’t know. I think maybe they were just careless and didn’t look carefully enough to notice that the truck in the picture was placed at 3 inches instead of 0.

- Teacher B: Or maybe some children are making both of these errors.

- Teacher C: So for re-teaching we will need to think about what fix-it strategies we could use for tomorrow …

- Teacher B: And they should be quite different depending on which error the student was making.

- Teacher A: Let’s work out what to do for the children who don’t know or don’t remember to zero the object on the ruler.

- Teacher C: We could make up some pretend rulers on oak tag where the first hash mark was at different distances in from the edge. We could cue the kids that they had to zero the object (say, we will have different size blocks for them to measure) and tell them that it won’t be easy to do because these are “trick” rulers.

- Teacher B: We could say you have to measure each object with a different one of the trick rulers and have the kids pass the rulers and the objects around the circle

- Teacher A: Maybe put kids in groups of five.

The scenario continues while these teachers analyze the thinking of children who answered C and D. (D is the “best" error. Can you tell why?). And the conversation moves to how to gather data about who made which types of error and how to manage the re-teaching. That can be done in minutes later in the afternoon by simply asking a few children to think out loud about how they solved the problem. This is also a golden opportunity for the teacher to share with students how s/he went about doing error analysis in preparation for teaching students, and how students can do the same with their own work.This thinking could also be a teacher looking at her own data and planning by herself. But imagine the power if teachers had regular collaborative opportunities with dialogue like this to examine data and plan how to re-teach a concept! Embedded in the practice above are essential beliefs about how to "do" school:

- "If some of the students aren’t getting it, it is my responsibility to do something different for them."

- "I have to get assessment information frequently [daily] to see when re-teaching is necessary."

- "If I take the trouble to do this assessment and to design re-teaching, the students who don’t get it now probably will get it."

These beliefs about student capacity show up in interactive teaching in very concrete and observable ways. They influence the spirit, the fiber, the character and commitment of the staff in the school to be persistent when the going gets tough with discouraged students or youngsters who are way behind. And they are evident in team meetings where they show up in dialog and statements one can hear. This is particularly true of the belief that all the students’ have the capacity to do rigorous material at high standards, even if they are currently way behind.

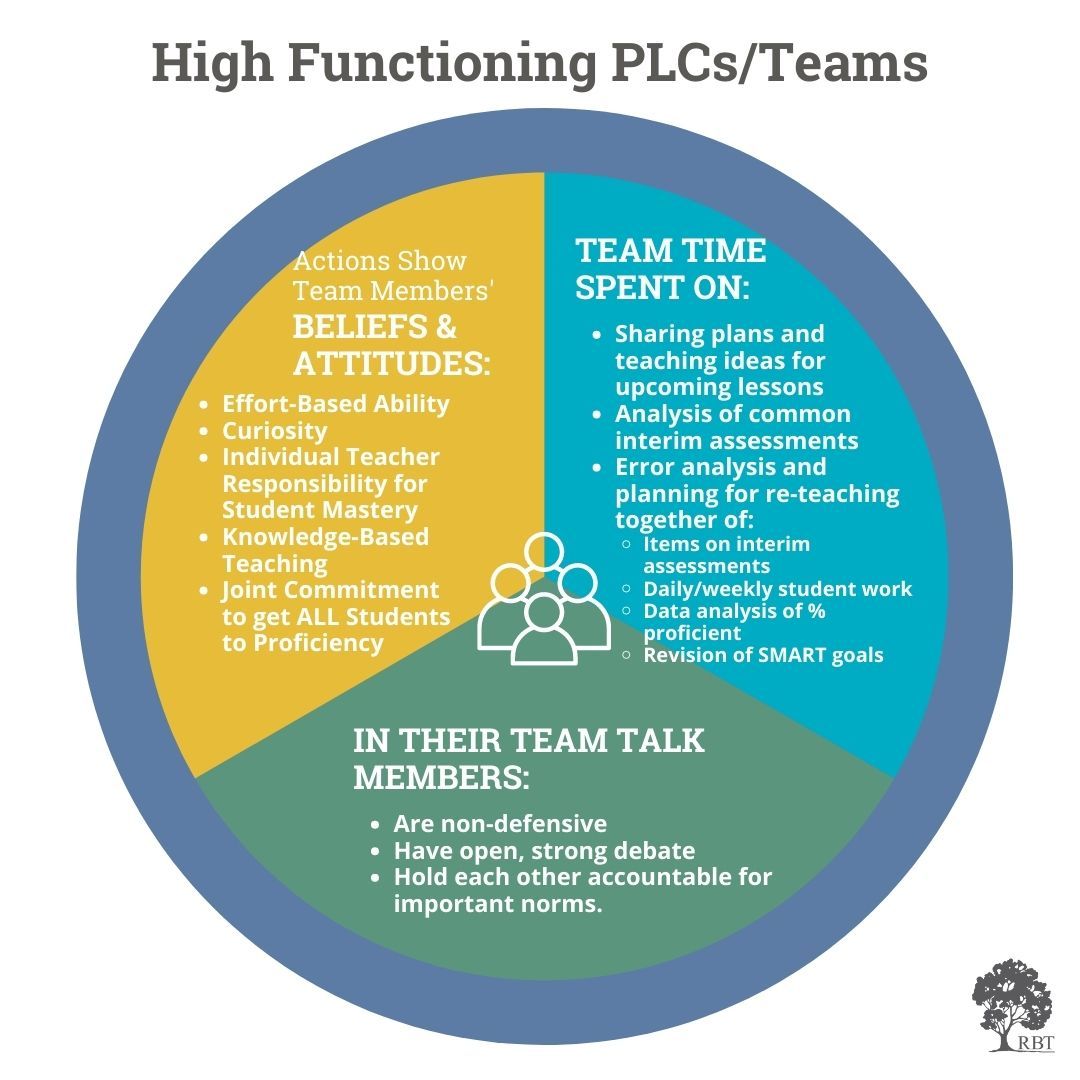

High-functioning teams spend much of their time on concrete issues of teaching and learning like the scenario above and like the items listed in the diagram above.

Other Worthwhile Uses of Team Time

Frequent Activities

- Do error analysis of student work for intervention and reteaching.

- Design together how to re-teach a certain concept or skill. (See 5th Grade PLC Video)

- Plan lessons together where they dig deeply into the content for concepts, sub-concepts, possible misconceptions, and evidence of learning that we will look for.

- Do “lesson-study” together.

Big Picture Items in the Background that the Teams Did Early in the Year:

- Figure out the precise alignment between your curriculum materials, state standards and your tests.

- Come to agreement about the most important 8-10 learning expectations for the students in a course and/or in a given unit -- what they are and what they really mean.

- Come to agreement about criteria for success and exemplars of student work that would meet the criteria. If we’re using a rubric, agree what products would score 1, 2, 3, 4 so we get reliable with one another on how we score student work.

- Set SMART goals for each curriculum

Leadership Support

It takes good leadership for a team to function like the three teachers described above, leadership within the team and leadership by the principal to develop those skills in team leaders.

- Skills at Data Analysis: Applying thee skills especially with item analysis from common assessments and interim assessments

- Concept-Analysis and Task-Analysis Skills: Knowing how to dig deeply into the content with the teachers around the table so you can all surface the concepts and sub-concepts under the task/item the students are struggling with.

- Generic Meeting Facilitation Skills: Keeping to the agenda, getting all voices in the room, etc..

- Skills to Make It Safe: Making it safe for faculty members to be vulnerable in front of peers… safe to invent new pedagogical representations…safe to disagree and debate…

- Skills and Courage to Face the Data and Push for Constant Measurable Improvement of Student Results: Setting SMART Goals for % of students proficient; also setting more narrow goals with commitment to try certain re-teaching approaches for particular skills/concepts and comparing results afterwards…

- Skills to Build and Practice Group Norms of 1) Trust, 2) Productive Conflict, 3) Commitment to Decisions, 4) Accountability for Interpersonal Behavior, and 5) Collective Results Orientation.

- Courage to Stand for Effort-Based Ability at Every Turn: Confronting peers appropriately for negative comments about children’s ability

How can we develop the habits of practice in enough faculty members so teams of teachers who share content perform this way as well as the skills of the leaders who support them to ensure this type of work remains a priority? Not by bringing in a consultant to teach them a “course”, though such courses can be a good starter. (This is not to dump on consultants. After all, I am one.) This work must be supported from a commitment from the members of the school community itself, and key players in that are members of the school leadership team.

The principal and the other members of the leadership team of the building are the only people who can accomplish this transformation; and transformation it is, because very few teams in any school function as described above, nor are there forces or supports in place to get them to do so.

Redefining the Building Leadership Team

So let us start by redefining the building Leadership Team in a school:

- The new charter of your leadership team (that is, its purpose, its mission, its main reason for being) becomes: improving the teaching and learning in every classroom in the building. Its primary purpose is not management of everyday business. (The paradox, of course, is that school business does not disappear just because you have redefined the leadership team, and so has to be handled anyway. Thus alternative times and formats for necessary communication around business need to be chosen.)

- The Leadership Team is composed of colleagues, under the leadership of the principal, who have a common vision of what good teaching and learning look like. You make a plan of action to achieve that vision in increments, and you implement that plan together.

- This team, working under the leadership of a clear and mission-driven principal, is the necessary condition for large scale improvement of teaching and learning. Principals can’t do it alone, however. Principals, as the instructional leaders of the building need multiple allies, many teacher leaders to improve teaching and learning.

- Get the “right people on the bus.”The leadership team should consist of those who have maximum access and influence over the teacher corps in the building. There are many different people who may, by virtue of their role, position, and status with their colleagues, fill this bill. One can compose a team of four to ten people from amongst:

- APs

- Dept. Chairs

- Instructional Specialists

- Coaches

- Team Leaders

- Counselors

- Resource/Sped teachers

- Lead Teachers

- Union Leaders

- ELL Coordinator

- Others

- A central job of a principal working to bring energy and direction to school improvement is to build a coherent Leadership Team – its charter, the skills, the focus, and the commitment of his/her leadership team members. It may be the main focus of the first year in a building. By the second year the leadership team meetings should evolve to a stage where the leaders are comparing notes on their leadership efforts just like we want teachers to share stories on their teaching efforts. Members are doing round table case reviews of supervision and coaching of individual teachers, problem-solving with and for each other, and functioning as a study group where they all learn new things about good teaching and learning and leadership together. The principal as the leader of this leadership team thinks of him/herself as the teacher to the group (and learner with them, of course.) Thus the principal plans these meetings just like planning a good lesson.

The principal and the LT members need to have a clear image of what error-analysis and re-teaching meetings look like and sound like. Thus principals working together in a training session should be the kick-off for this work. Principals might, indeed, benefit from a formal PD course on the scenarios described above. They themselves, however, should be the “course leader” and facilitator in the ensuing stages for their own building. This is principal as “teacher” among colleagues, or principal teacher, which is the origin of the title “principal” to begin with.

Each member of the Leadership Team should see, participate in, and practice leading error analysis and re-teaching meetings of teachers. At the outset the principal could have each member of the leadership team bring a packet of recent student work from a classroom (one can invite the teacher too, as an observer or a participant.) The principal leads the error analysis and re-teaching meeting just as if it were a grade level or common-subject group. Note: the principal is modeling risk-taking, not being expert at doing this, and commitment to find a way for the student(s) to learn the item. Other early-stage actions are for the principal to lead an actual grade or subject meeting into error analysis and re-teaching and have leadership team members observe and debrief with the principal, always modeling and being explicit that “we’re trying to learn how to do this important thing.” Then other LT members get into the cycle with other members of the Leadership Team observing.

Leadership team members then move into a role of being present at all team meetings of teachers who share content. They decide differentially how strong a role to play at these meetings, depending on the level of development of that teacher team. Presence as well as intervention, guidance, and modeling productive team meetings for error analysis and re-teaching is not the only lever, but it is a most important one for influencing teaching and learning in any school.

It would accelerate school improvement and good work all over the country at closing the achievement gap if the focus described here were incorporated in programs for the training and certification of school leaders.