The Courage to Lead

Courage can be learned.

There are case studies available all over the country that show that individual schools and occasionally whole districts with many children in poverty get very good achievement results – in some cases as good as or better than nearby affluent suburbs

This news is inspiring and gives hope; it is also discomfiting, because we quietly wonder if we know enough or are good enough to get the same results. And reading about what they did (e.g., Michael Schmoker’s, The Results Fieldbook) somehow doesn’t give us the tools to work the miracle. How can we think about this conundrum?

It takes courage and skill to move a school forward because people are accustomed to being left alone; and progress means getting people to change their practices and behaviors. Thus, when one begins the improvement process, some staff will experience the changes that we bring forward as strange, or unnecessary, or disruptive, or even ill-conceived. (And occasionally they will be right!)

Another reality that demands courage is facing the fact that we will make mistakes along the way. We will experience confusion, uncertainty, and anxiety from time to time. And all of that could be avoided if we just went on with business as usual: managing the building, doing discipline, and handling daily problems or if as a central staff person we went on handling crises, doing our reports, and keeping up with staffing issues!

And our students who are losing out would continue losing. So just go on managing?... Can’t do it.

In addition, “leadership for improvement” can be lonely and make us unpopular with a segment of our own folks. The results seem uncertain and we will be risking failure on a regular basis. People who like the changes may be silent, letting us know in indirect ways that they are depending on us to keep going anyway and carry the ball against the opposition!

So will the children.

Why would anybody want to experience all that if such is the cost of courage? Because it can give meaning to our lives and work beyond what we may have known before…and a feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment that’s better than any high.

PROPOSITION 1

Despite all our good work in recent years, there is a large gap between what our students are achieving and what they need to achieve and could achieve.

There are others schools and districts that have significantly elevated student achievement in similar conditions. It can be done.

Raising student achievement significantly means large-scale changes in teaching practice at the classroom level and high-level teamwork at grade levels. Almost every improvement initiative (including common assessments, Beginning Teacher Academy, PD workshops, position of Instructional Specialist/Coach) aims directly or indirectly to improve classroom instruction.

PROPOSITION 2

Virtually all of the reform initiatives of the late 20th and early 21st century (like teachers doing data analysis of student results, like the DuFours’ “Pyramid of Interventions” for low-performing students, like the teacher coaching structures appearing in so many of our schools) are grounded in a few beliefs. These beliefs, however, are rarely an explicit part of dialogue – dialogue among leaders, dialogue among staff, or especially dialogue between leaders and staff – yet it is important that they be made explicit. As we lead for specific changes in practice, we must at the same time surface the beliefs from which they stem.

These Beliefs are:

PROPOSITION 3

Without leadership to change (read as to improve) classroom instruction and school practices, leadership that calls for – more, summons, encourages, supports, and with perseverance pushes for key changes in practice – improvement of results for students will not happen. The inertia and comfort of conventional teaching practices are too strong. Among the many changes in practice that are called for, here are a few examples:

- Nightly error analysis and inventive planning for reteaching material to those students who didn’t understand the first time around

- Constant and broad checking for understanding during instruction Frequent, detailed, nonjudgmental feedback to students that helps them identify and improve performance

- Teaching students to believe in their own capacity to grow ability

- Teaching students how to exert effective effort when learning doesn’t come easily

- Frequent analysis of student results from common assessments by teams who actively help each other design teaching and reteaching approaches

- Using a variety of cognitive tools to make ideas more clear and vivid

The improvements in instructional practice that are needed challenge the very job definition of teaching carried by millions of practitioners. This is a double whammy:

- Changing deep and previously unchallenged beliefs, and

- Undertaking the massive change of teaching practices that proceeds from the new beliefs

The scale of this change and the very large inertia of sticking with the status quo combine with the identity threat to millions of teachers whose self-esteem is invested in continuing to do business as they always have. School principals who rise to this challenge require a high level of stamina, since resistance will surely come from some quarters in the staff, and this inevitably raises normal human fears about the consequences to the leader as he/she pushes for change.

The good news, however, is that we have a great mass of committed teachers who already operate from the seven beliefs above, and they are seeking the leadership that will give them the challenge and the resources to bring children to new levels of achievement. Indeed, they will respond with commitment and inventiveness when we give them both the support and the time that are required.

PROPOSITION 4

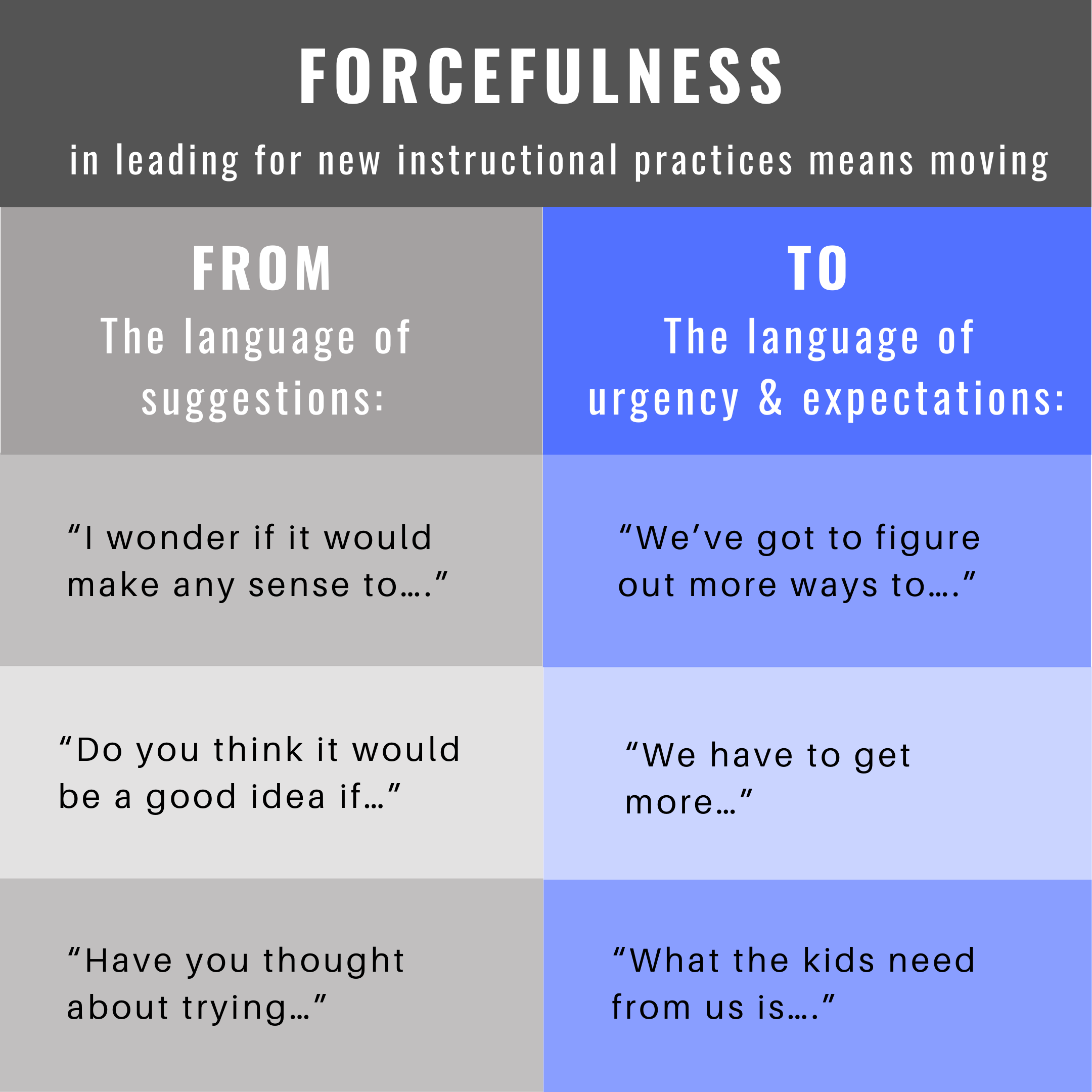

“We can act our way into new beliefs,” says Michael Fullan. Indeed, we can. It’s hard to tell which comes first, the chicken or the egg. They do, indeed, go hand in hand. Nevertheless, some of these important changes in teaching practice have to be started for the beliefs to begin changing. Beliefs change when teachers start to see results. So, there is a certain forcefulness required from leaders to accelerate the pace of adopting these new practices.

This forcefulness must be balanced with:

- Acknowledgement that the changes are difficult

- Humility about not knowing how to do them all

- Planning together for how to move

- Support for learning how to do the new practices

- And especially listening to the views and worries of the staff members we are working with.

PROPOSITION 5

Large-scale improvement of instruction also calls for explicit discussion of the key beliefs. The chicken and the egg sit together in the barn. We lead for specific changes in practice, and at the same time surface the beliefs from which they stem. When we contemplate leading for significant instructional improvements and talking about the associated beliefs, every one of us

inevitably faces certain fears:

- Fear of being disliked, being discounted, or losing relationships:

- Version A – “If I bring this belief up, it will be taken as an accusation that people are not doing their job, are not good enough. I can’t face that. I want to be perceived as supportive, not blaming. A leader is supposed to be supportive and positive.”

- Version B – “I want to be one of the crowd, included; not an outlier, out of-step, somebody who ‘makes our lives harder.’”

- Version C – “She’s too idealistic, too young.”

- Fear of conflict: “If I bring this belief up, it will start polarizing debates that will be divisive. In fact, it may provoke a firestorm that will consume a lot of energy, mine as well as others’. I don’t like conflict like this, nor know how to handle it.”

- Fear of failure: “If I bring this belief up, it won’t do any good. Changing attitudes is hopeless. I will fail and feel horrible.”

- Fear of being fired: “If I bring this belief up, it will lead to forces being mustered against me and I will lose my job…like ‘he’s making us look bad.’ ”

- Fear of being seen as incompetent: “If I bring this belief up, I’ll be shown as the emperor with no clothes…because I don’t really know exactly what to do to make this belief come true.”

- Fear of being shallow: “If I bring this belief up, I will be inauthentic because I’m not sure I believe it enough myself!”

- Fear of hard work or running out of gas: “If I bring this belief up, I’ll have to work harder than I want to. It will exhaust me.”

It takes courage to push through these fears…courage to face resistance and to cause the inevitable discomfort. But courage can be grown; it’s not inborn. Courage can be developed. Courage can be learned. If we want to be thought of as courageous leaders who get results for children, we can “make it so,” as Captain Kirk used to say. Courage is not being fearless; it is recognizing one’s fears, pushing through them, and acting anyway. None of us yet has all the skills one would want to lead for a “breakthrough” school or district. But we have enough. We’re ready to push to the next level.

PROPOSITION 6

What does it take to grow courage?

- Get clear on what your deepest and most strongly held beliefs are, and how strongly you hold them.

- Name your fears and stand in the middle of them.

- Decide what you’ll hold yourself accountable for and what you won’t hold yourself accountable for (in your behavior, not the outcomes of the process).

- Develop your self-awareness and capacity to be mindful in the middle of stressful moments.

- Learn central skills about communication and about change.

- Work the network of your contacts and your supervisors to communicate your plan.

- Have a professional support group for yourself for practice and feedback.