Essential Elements of a Well-Structured Lesson

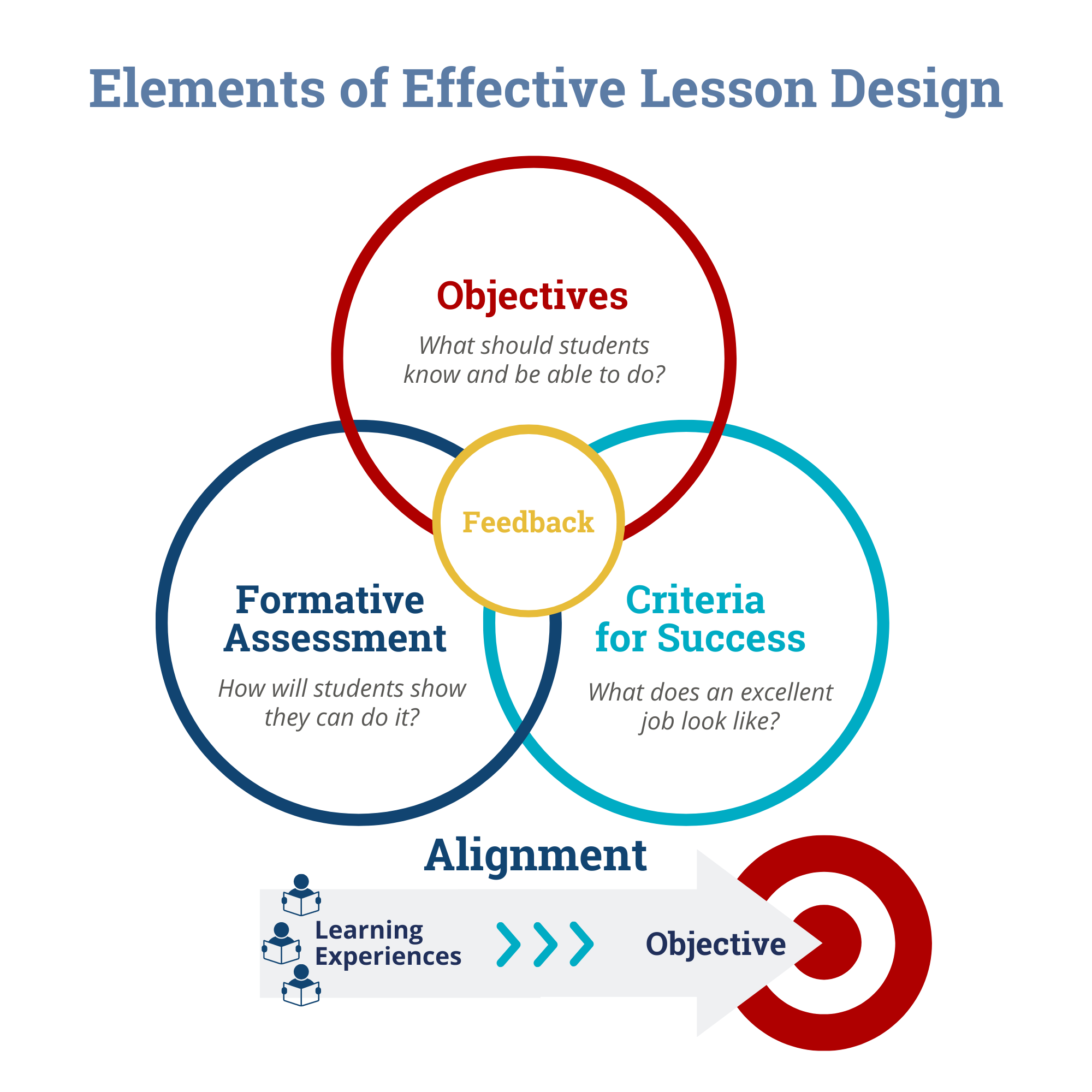

Every rubric in the country lists some form of “Well-Structured Lesson” as an element of successful teaching. But what does that mean? The core is four elements which actually need one another for the lesson to achieve the results we want. That is why in the diagram attached we show them as intersecting circles.

There are intimate connections between these four elements of well-structured lessons as well as the alignment of the activity with the objective. Therefore it can be futile to study any one of them in isolation without integrating what we learn about all five.

What we present in this article and accompanying video is the meaning of each of the five and then the way in which they affect each other to create that “well-structured lesson”.

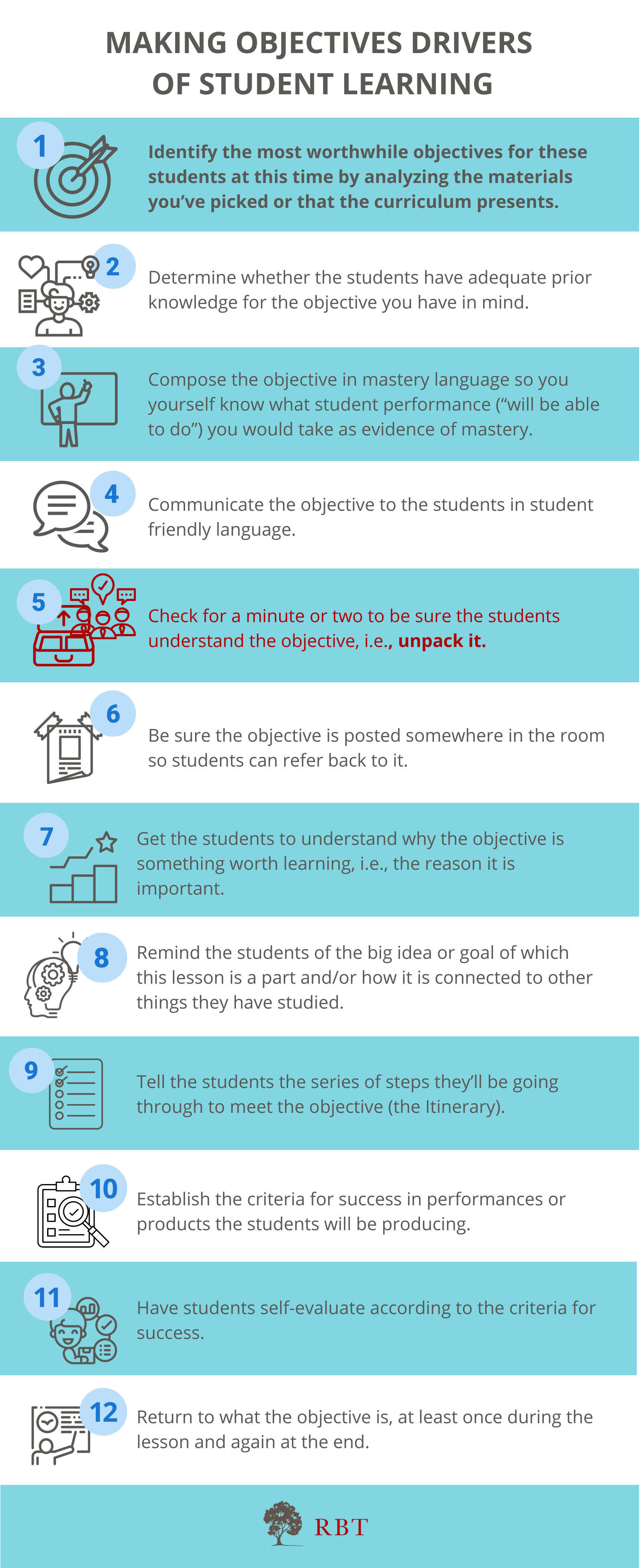

Objectives

This is, of course, what the students will know or be able to do (or do better) at the conclusion of the lesson. There are about a dozen facets of objectives that are worth knowing (like how to articulate them in student friendly language). But I want to highlight two crucial elements here: that students understand what they mean, and they must be worthwhile and appropriate for the students. It’s no good communicating an objective if the students don’t understand it, because the purpose of communicating it is so they (and we) can focus their attention on meeting it. And it’s no good communicating an objective that is too hard, too easy, or for which students do not have adequate prior knowledge to tackle it.

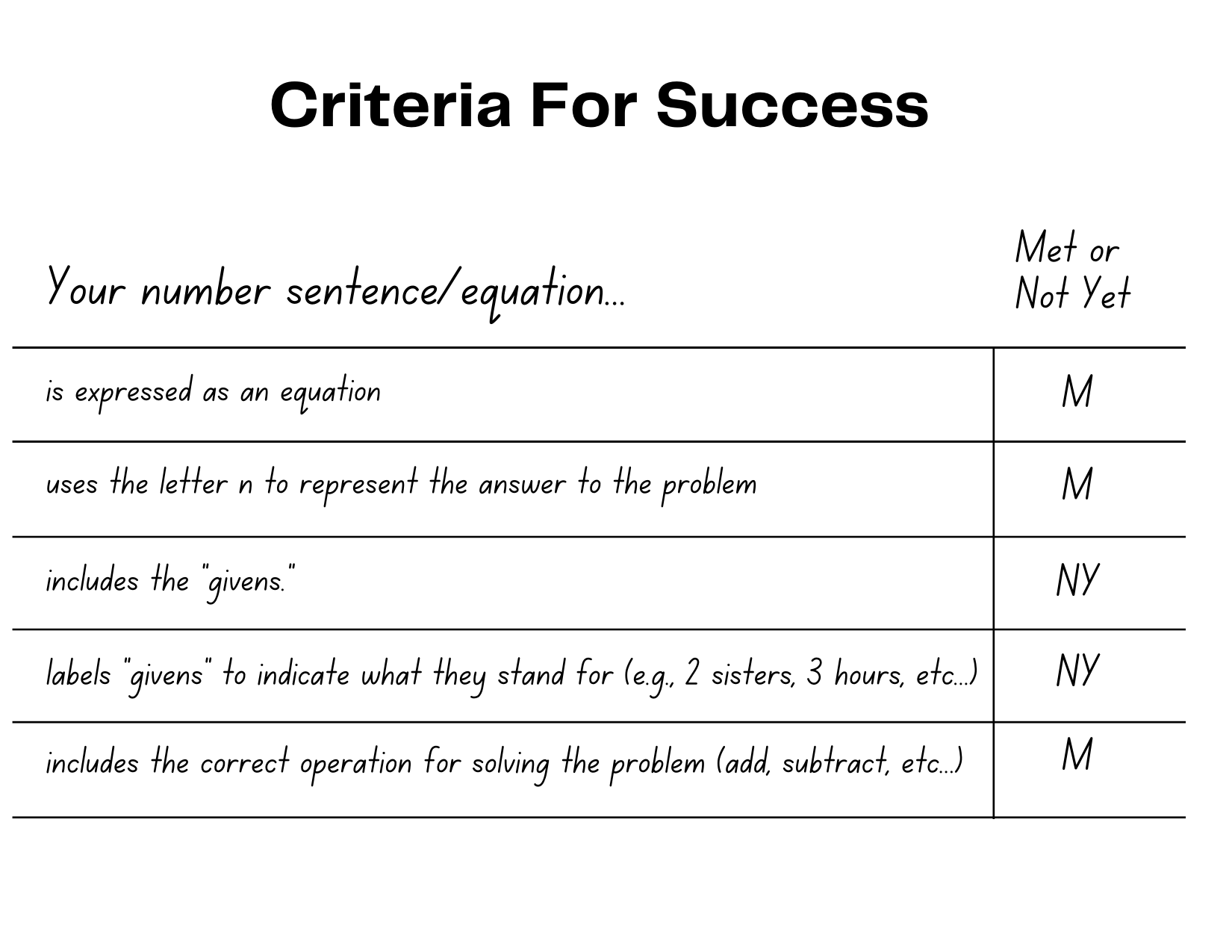

Criteria for Success

These bulleted criteria really define what the objectives mean, because they are the items or the qualities that need to be present in the final product to say a student has met the objectives. Co-developing the criteria with the students as in the video on pictographs featured in the accompanying video, is a strong way to get the criteria understood and remembered. Next, posting them on a public chart for ongoing reference helps students remember what they are working toward. Similarly, having an exemplar of a final product is very helpful for students. Going through the exemplar with students and having them identify specifically where each criterion is present, is even better.

Feedback

The students need to be able to use feedback to improve their work. That’s the point. They can use our feedback if we report specifically which of the criteria they have met and which ones they haven’t. “Report” is what we’re doing. Now, we can be encouraging in the way we do that reporting, but the communication needs to be without blame or negative judgment. “You have numbers 1 and 2, take another look at number 3 to see what you’re missing.” When the criteria are clear, feedback does not just need to come from the teacher, it can come from peers doing peer review according to the criteria or from the students themselves doing self-evaluation.

Formative Assessment

We as teachers are doing a running check, all the time, to see if the students are following. If they are not, we are going to do something about it – make a group for re-teaching later, or pause the lesson and put students in pairs of triads to explain to one another, or any number of other fix-it strategies to deal with student confusions. The main thing is that we have to get a reading that is alert to student confusions so we can address them through our teaching before they compound and create frustration or discouragement in our students.

There is an intimate connection between the 4 elements. Studying any one in isolation without considering the others is an incomplete process. It also doesn’t give us the fullness of the simultaneity with which we need to not only design and implement effective lessons, but also the data we need to gather during the delivery of a lesson to inform our next steps.

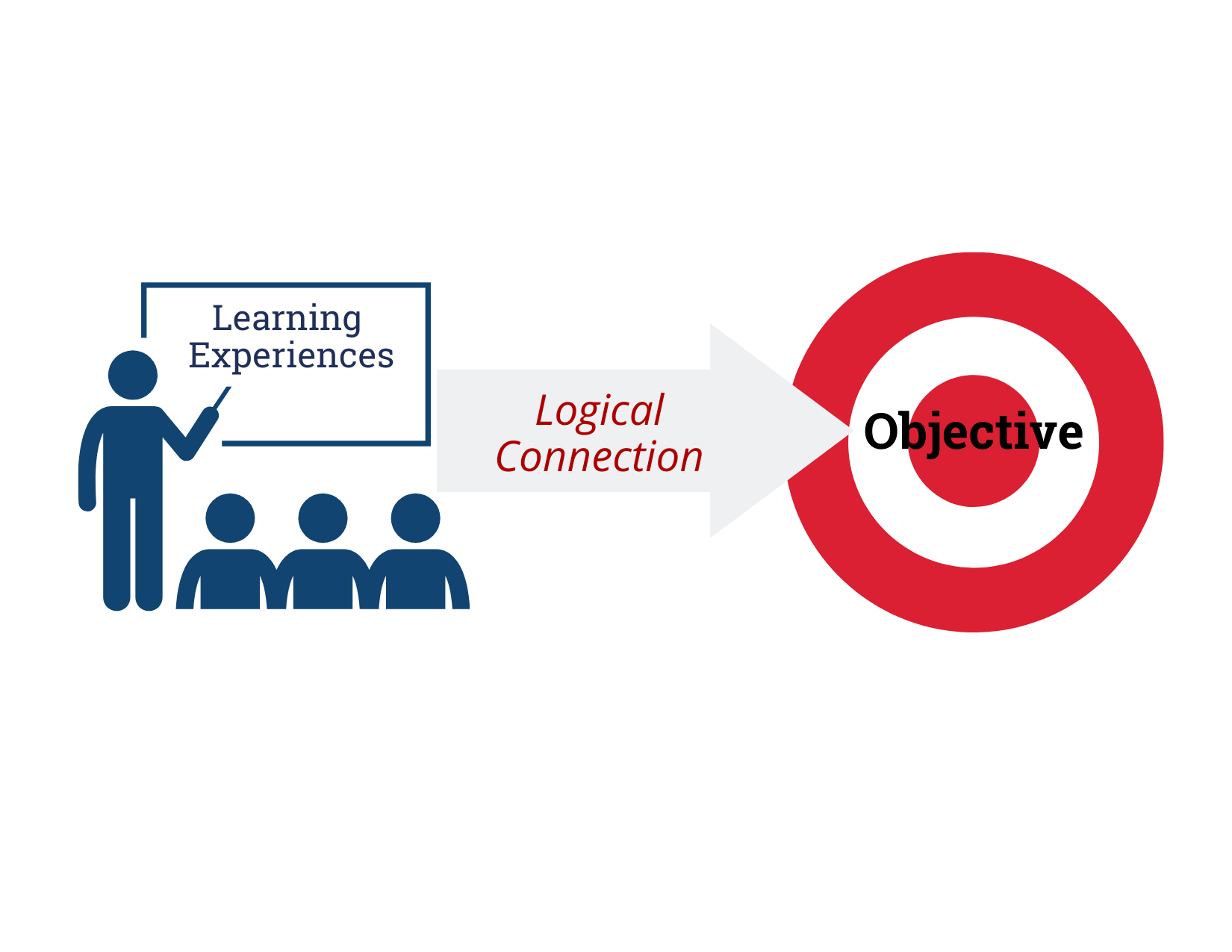

Alignment

Will the students learn the learning you want them to learn if they do the activities you have asked them to do? This is not a frivolous question. It’s a question that gets us to focus on the center of the objective. The question asks us to temporarily peel away the other valid items that may be on our minds, like student interest, active engagement, lively talk, use of visuals…whatever! Not that those items are irrelevant – certainly not. But what about the logic of the lesson? Will watching a dramatic video of the successful reentry of an Apollo space capsule help the students focus on how NASA creatively solved the heat shield problem? Will removing the gooey pits from the pumpkins before Halloween and cooking them get your kindergarteners familiar with the 10s and 1s concept you want to introduce about place value?