Riverkeepers: School and District Leaders Use High-Leverage Strategies to Keep Vital Streams of Books Flowing

Just as riverkeepers protect precious waterways, effective school and district leaders make it their mission to keep steady streams of compelling books flowing continuously into every classroom. |

A. Ward and M. Hoddinott |

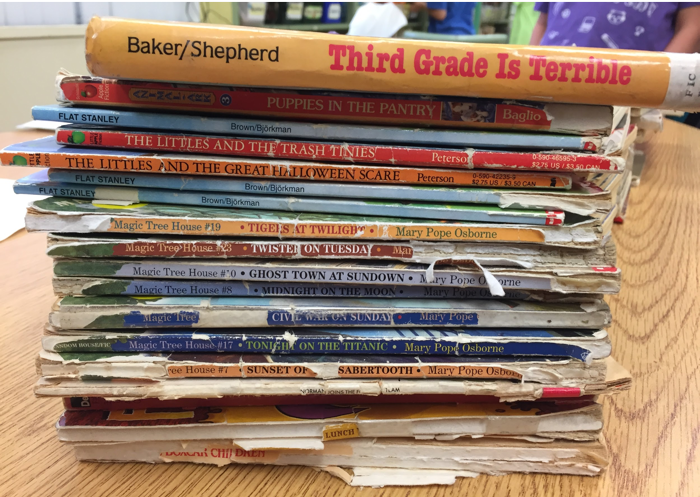

Third grade teacher Liz Johnson puts a copy of Dog Man: A Tale of Two Kitties into Gabriel’s hands just in time for Memorial Day weekend. Gabriel has been on the move since the original Dog Man unleashed a stream of voluminous reading, and Liz recognizes the need to maintain his momentum. But it’s no accident that she has a fresh copy of Pilkey’s latest. The timely delivery of Gabriel’s next-up book is the final link in a chain of deliberate actions taken by committed educators at every level of the organization. Just as riverkeepers protect precious waterways, effective school and district leaders make it their mission to keep steady streams of compelling books flowing continuously into every classroom by...

Budgeting for Classroom Libraries as Generously as Possible.

- Riverkeeper leaders know the research on the benefits of voluminous, engaged reading. They cite it persuasively and advocate to establish and maintain robust book budgets for their districts and schools.

- These leaders monitor spending carefully and ensure that every penny earmarked for books is spent on books. They hold funds sacred and fend off requests for other unprioritized materials.

Allocating the Money for Books, Glorious Books!

- Riverkeeper leaders know that readers thrive on a diet of authentic literature of all kinds. They make sure that the entire budget is spent on real, irresistible books, magazines, and ebooks.

- These leaders wisely remove English Language Arts from their districts’ multi-year textbook allocation cycles and instead provide ELA teachers with steady annual allocations. Any dry spell in the flow of book money devastates school and classroom libraries and plunges readers into book deserts.

- Riverkeeper leaders distribute responsibility for book ordering by budgeting in tiers. In Mamaroneck, for example, we allocate money as follows:

- A substantial allocation directly to classroom teachers in order for them to “build classroom libraries for the children they expect and customize libraries for the children they meet.” We divide this allocation into three ordering periods across the year with clear timelines and ordering procedures.

- An allocation for school administrators to apply to priorities specific to their buildings. When classroom libraries are inventoried, administrators develop priorities based on the ranges and conditions of collections as well as the alignment of books and readers in each room.

- An allocation at the district level administered by the literacy ambassador. Each year, she selects appealing collections of new books for each grade level and infuses them directly into classroom libraries, accompanied by video book-talks to familiarize teachers with the selections. These infusions ensure some degree of consistency across classroom libraries and ensure that teachers are kept informed of publishing trends, new series, etc.

- When monies are tight (and they always are), riverkeeper leaders reconsider the well-intended practice of providing a schoolwide “Book of the Month” to all staff. While this popular ritual provides common ground, stimulates discussion, and leads to colorful bulletin board displays, it is tremendously costly (60 staff x $10 books x 10 months = $6,000 which could instead fully renovate two classroom libraries or supply 30 classrooms with $200).

Streamlining and Demystifying the Ordering Process

- Riverkeeper leaders work closely with business offices to understand district purchasing procedures, identify approved vendors, and grasp the steps necessary to order specific titles rather than prepackaged collections of books. They educate bean-counting colleagues on the need for nimble responsiveness to reader interests; they suggest ways to expedite the procurement process such as open purchase orders with local approved vendors.

- These leaders demystify ordering procedures: they explain how to order hand-selected books and provide teachers with order forms containing pre-entered vendor information. Knowing that additional monies sometimes become available with short turnaround time as the year unfolds, leaders keep ongoing book wish lists and encourage teachers to do likewise.

- Riverkeeper leaders identify passionate, knowledgeable book mavens and provide opportunities for them to support teachers in knowing and ordering the latest and greatest titles as well as books for children with niche areas of interest.

- They familiarize teachers with perennially reliable sources of new titles and include book-talk booking rituals at faculty and grade level team meetings.

Conducting meta-analysis of over 50 reading research studies, Stephen Krashen found that the single greatest factor in reading achievement (even above socio-economics) was reading volume--how much reading people do. |

Donalyn Miller“I’ve Got Research. Yes, I Do. I’ve Got Research. How About You?” (February 8, 2015) |

A Conversation with Jon Saphier and Annie Ward

Annie and Jon cover what it takes to turn striving readers into thriving readers one book at a time.

Tracking Spending and Following Up

- Riverkeeper leaders audit teachers’ purchases to track spending patterns. They highlight teachers who have purchased books with specific children in mind and follow up with teachers who have not spent their allocations. When book flows ebb, libraries stagnate and kids suffer!

- Riverkeeper leaders look downstream daily. They peruse classroom libraries; they confer with children about what they’re reading; they look in book boxes and backpacks. When classroom libraries are not vibrant and children are not reading voluminously, leaders identify and remove the obstacles that may have blocked flow (e.g., unreliable allocations, confusion with ordering procedures).

The book desert phenomenon is particularly striking in high-poverty tracts; it is only somewhat ameliorated in borderline communities. Still, neither of these community contexts comes close to book availability in higher income communities (e.g., estimated to be more than 300 books per child), nor do they provide the quality of selection and choice that previous research has shown to be associated with reading achievement. |

Neuman and MolandBook Deserts: The Consequences of Income Segregation on Children’s Access to Print |

Weeding Routinely

- Just as rivers need to be dredged, mucky old books must be weeded out to make way for appealing new arrivals. Riverkeeper leaders encourage healthy turnover by ensuring that books flow reliably into classroom libraries, by clarifying weeding criteria and procedures, and by providing time for teachers to discard dated, obsolete, MUSTIE books.

Protecting and curating the flow of books into classrooms and kids’ hands is an ongoing, vital responsibility. Even as they track every penny, riverkeeper leaders internalize Donalyn’s powerful admonition that “It’s better to lose a book than to lose a child.” Whether a lost book is gathering dust under someone’s bed or has become a dogeared favorite, riverkeeper leaders channel Elsa and “let it go,” budgeting for its replacement. They know it is penny wise and pound foolish to impose penalties for lost books or to curb children’s borrowing privileges. (Incidentally, Gabriel devoured A Tale of Two Kitties over the long weekend, and Liz cheerfully reported it was the second copy she had purchased for her class, using her allocation to fuel its viral popularity.)

The more minutes of high-success reading completed each day is the best predictor of reading growth. |

Richard Allington |

Annie Ward on being a literacy leader

View the full interview or select a smaller selection to review.