The Skillful Culture Builder

The following is an excerpt of a chapter from Jon Saphier's forthcoming book on High Expertise Teaching and how to get more of it in more places, more of the time. Due out in 2023.

I’ve used the term “role” in describing the new role of the principal, but what I really have in mind is a trio of parts, the most central of which is learning leader – one who models learning, but also shapes the conditions for all to learn on a continuous basis….So the principal’s role is to lead the school’s teachers to improve their teaching, while learning alongside them about what works and what doesn’t. |

Michael Fullan, 2011 |

It seems like on every level these [highly effective schools] were organized with teachers' professional needs in mind ... teachers constantly work with and learn from each other. The schools are designed to build collective capacity. |

Susan Moore Johnson, 2020 |

Four years of public school teaching…and ten years as a principal…convinces me that the nature of the relationships among adults who inhabit a school has more to do with a school’s quality and character, with the professionalism of its teachers than any other factor. |

Roland Barth, 2001 |

Since Roland Barth’s comment, twenty years of research have proven him correct. This chapter reviews that research, but more importantly, shares the practical knowledge of how effective leaders build strong Adult Professional Cultures through their daily interactions with others. The first half of the chapter discusses the background and rationale. The second half (starting p.12) provides the details of the actions and moves that build it. We have a significant amount of literature in recent decades describing the elements of a vibrant adult professional culture, that is, what one can see and hear when it is strong. I hope this monograph will make a contribution by focusing on what successful leaders actually do to transform a weak culture into a highly effective one.

Both And…

If we pursue High-Expertise Teaching fully understood without also creating strong Adult Professional Culture, we will get points of light rising from a flat environment lacking energy and synergy between professionals. If we do the opposite, pursue Adult Professional Culture without the guiding focus of High Expertise Teaching as the main thing to learn in a “learning organization’, we will produce a lot of energized people who strive without coherence. Therefore we will not attain the holy grail of more High Expertise Teaching. If we pursue both by design, then we can develop the structures and routines that get equity and excellence for all.

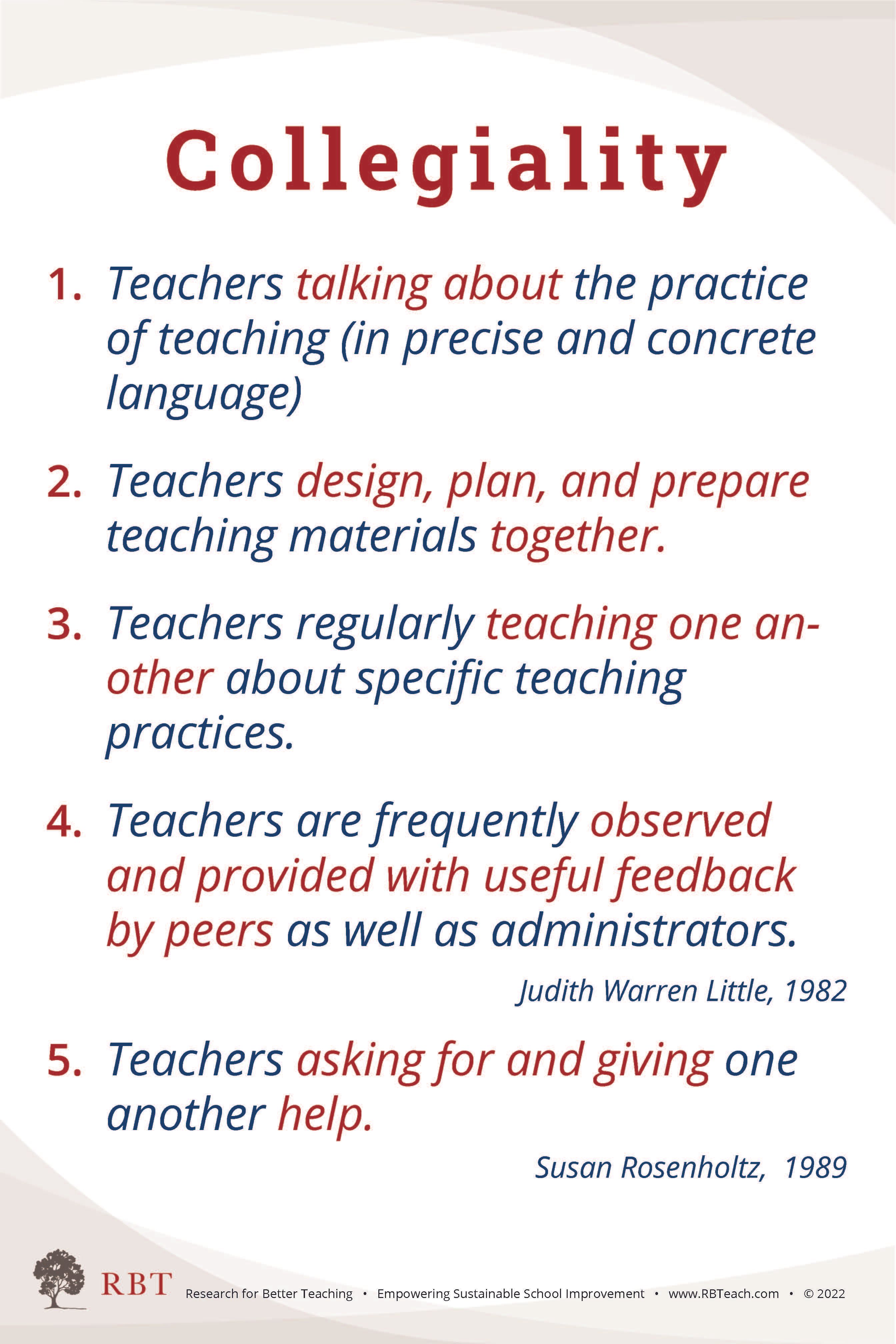

The inclusion of this chapter derives from the definitive research findings of the last 40 years about the significance of adult working relationships and the beliefs behind them for any sustainable improvement of anything in schools. Judith Warren Little started us on the pathway with “Collegiality” precisely defined in 1982. Matt King and I elaborated that concept in 1985. And since then an all-star team of researchers have deepened it continuously (see references in this chapter). Though this chapter comes fifth in the book, it may well be first in the foundation for developing High Expertise Teaching within a district given the current obstacles to having policy drive improvement.

History

I had an experience in 1982 that forever changed my view on school improvement. I was asked to give a workshop in two schools in the same district on formative assessment. In the first school, the workshop was warmly received, and when I returned two weeks later, teachers had been trying out many of the strategies enthusiastically. I covertly patted myself on the back.

At the second school, there was lackluster response, and no one was trying out anything as far as I could see. I wracked my brain to see what I had done differently or poorly at the second school, and soon realized that the reaction in neither school had anything to do with me (one of many humbling experiences in my years as a staff developer). It had to do with the adult culture of each school. The first school was a place where teachers were eager for learning, in close and frequent communication with one another, and constantly experimenting with new techniques to get better. Soon another powerful experience gave me some powerful back-up for that.

I was a member of a magazine club that same year with Roland Barth, Kim Marshall, Matt King and Bill Dandridge. We would rotate to one another’s houses once a month and each shared an article in which we thought there was something significant about teaching, learning, or leadership. In the fall of that year, Roland shared Judith Warren Little’s 1982 article in The American Education Research Journal titled: “Norms of Collegiality and Experimentation: Workplace Conditions of School Success”. What an eye opener!

Little was a descendent of the Effective School researchers of the 1970s, renowned scholars such as Ron Edmonds, Larry Lezotte, and Wilbur Brookover who had identified schools that did well for children despite seemingly harmfulcrippling neighborhood and family conditions.

The Effective Schools research came up with “Effectiveness Factors”, for example high expectations; clean, safe environment; and strong leadership, helpful, no doubt, and eye-opening to gainsay the Coleman Report (1966) of the previous decade. The Coleman Report indicated schools were helpless in the face of negative socio-economic family and neighborhood conditions.

Similar to those scholars, Little identified schools that succeeded against the odds and compared them to those that did not. She, however, had a different focus question. She didn’t examine aspects of their programs, rather she asked how the adults treated one another. So, she would hang out in the teachers’ lounge and see what people talked about. She would arrive early and stay late and see what the adults were doing and with whom.

What she found was that the schools that did better for children had regular patterns of adult interaction that she could observe:

- Teachers engage in frequent, ongoing, and increasingly concrete and precise talk about teaching practice (common language)[1]

- Teachers plan, design, research, evaluate, and prepare teaching materials together

- Teachers regularly teach one another about specific teaching practices

- Teachers are frequently observed and provided with useful (if potentially frightening) critiques of their teaching by peers as well as administrators

When Little was done, she decided she needed a word to define this four-attribute environment, and choose “Collegiality” as the word. Thus, a professionally defined term was born. It has, unfortunately lost its precision of its meaning, though the term is still widely used these days.[2]

In her 1989 study, Susan Rosenholtz added a fifth factor to these behavior patterns of adults in effective schools: teachers’ willingness to ask for and give one another help. (Giving advice can be as risky as asking for it.)

To go back to my magazine club, we were all quite taken with Judith Warren Little’s findings, probably because they reinforced what we’d all observed informally in our own practice. And it became an incentive for me and my colleagues at Research for Better Teaching to study conditions among the adults in schools where we worked, and to begin formally assisting leaders in developing these conditions. It also led to my first venture into publishing in the culture field with Matt King in Educational Leadership Mmagazine (Saphier and King, (1985).

The purpose of this chapter is to lay out the details of observable daily behavior of leaders who build the strong, positive cultures described above, for example the details of how leaders build trust. This is a practical monograph about what to do and different ways to do it.

Precursors

Willard Waller (1932), Phillip Jackson (1968), Dan Lortie (1975), and Seymour Sarason (1982) wrote about the conditions of teaching in ways that made clear what the obstacles were to strong adult culture: isolation, privatism, individualism, teachers’ social status, the “dailiness” of school life” and so on. Ann Lieberman and Lynne Miller (1979) were the first authors I came across who took on the actual aspects of positive adult culture that they saw as healthy and required for school improvement.[3]Next came Judith Warren Little (1982). Simultaneously, two widely-read books on corporate culture, one by Peters and Waterman and the other by Deal and Kennedy, both in 1982, started a cascade of books in the business world about organizational culture and its connection to company success.

Educational studies of adult culture started rolling out more frequently in the 90s (e.g., see Joyce 1990, Newmann and Wehlage 1995). So, for at least twenty-five years, we had major authors advocating for the importance of Adult Professional Culture (e.g. Hargreaves and Fullan, 2012), and also some excellent how-to guides produced for educators by practitioners such as Gruenert and Whitaker, 2015.The argument was simple: there was a cause and effect chain. Strong Adult Professional Culture (APC) leads to more teaching expertise in more classrooms for more children more of the time, because it creates the kind of deep collaboration and use of data that supports constant learning about teaching practice. Thus, High-Expertise Teaching leads to better learning for students.

Finally, a study by Daly et al study (2014) provided direct school-based data on the connection between strong cultures and student achievement. This and the earlier studies also built a strong foundation for the argument that would come later: that the range and sophistication of teaching expertise is far larger and more complex than the voting public and policy-makers realize. This complexity explained why deeply collaborative cultures were necessary for the kind of problem-solving in which true professionals engage. Educators help each other analyze the nature of learning issues and respond with the correct choice from their repertoires rather than applying some “best practice”.

Be the First to Know

This is a sample from a chapter from Jon Saphier's new book on High Expertise Teaching due out in 2023

Learn more about the full contents of the book and sign up to be notified of its release in 2023